Day 127

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post will feature the next Grade 2 Common Core Math Standard listed in blue, followed by its ambient counterpart as practiced by Waldorf Education and Math By Hand.

Operations and Algebraic Thinking 2.OA

Work with equal groups of objects to gain foundations for multiplication.

3. Determine whether a group of objects (up to 20) has an odd or even number of members, e.g., by pairing objects or counting them by 2’s; write an equation to express an even number as a sum of equal addends.

Multiplication is learned alongside addition, subtraction, and division in Grade 1. So there’s no need to gain a foundation for multiplication since it’s been established from the beginning. Knowing the times tables is an indispensable essential that needs to be firmly in place by the middle of Grade 3. Waldorf and Math By Hand introduce long multiplication and division mid-Grade 3, and fractions at the beginning of Grade 4. These and all other math functions cannot be learned successfully without total times tables fluency.

For this reason, regular practice with the 2, 5, and 10 times tables through movement, games, art, singing, and patterns begins early on in Grade 1. Math By Hand Grade 2 begins with an intensive times tables block. One of the first projects is the construction of an oversized, colorful wall chart of all 12 tables. A simple folding exercise with large poster paper yields 144 folded squares. The children fill in all the rows they know: 1, 2, 5, and 10, then learn that since 11 is just double numbers, that row can be filled in as well. It’s empowering to see so much of the chart completed! Then a reference chart is used to help fill in the rest.

Counting by 2’s has been happening for a while now, and when multiplication and addition were compared in Grade 1, the relationship between the two made it apparent that 2 times any number would look the same as adding those same numbers (including showing how an even number is a sum of equal addends). Glass gems or other manipulatives were used to show this, then after seeing the equations concretely in this way, they were written as a last step in the process. Of course this continues in Grade 2 as a review, before moving on to addition and multiplication with regrouping.

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of knowledge as a worthy goal. Tune in tomorrow for more Common Core, along with its ambient, Waldorf/Math By Hand counterpart.

Tags:

Day 126

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post will feature the next Grade 2 Common Core Math Standard listed in blue, followed by its ambient counterpart as practiced by Waldorf Education and Math By Hand.

Operations and Algebraic Thinking 2.OA

Add and subtract within 20.

2. Fluently add and subtract within 20 using mental strategies. By end of Grade 2, know from memory all sums of two one-digit numbers.

The morning circle and skills practice are perfect opportunities to practice this standard. Note, as always, that all 4 processes are worked with at once. During morning circle, which is a lively way to start the day in the Waldorf classroom or homeschool environment, much math practice happens, joyfully and with movement!

Because the block lesson system focuses on one subject at a time as a 1 1/2 to 2 hour main lesson for 3-4 weeks, it would not do to “forget” math during the other blocks. So the skills practice time (after recess and before lunch) of 20 minutes to 1/2 hour in Grade 2, affords an opportunity to keep up math skills between math blocks. This can be a balanced mix of written work and mental math with movement.

Here is a sample morning circle from the Math By Hand Grade 2 Daily Lesson Plans book. (There are four 15-day blocks in Grade 2, with two morning circles supplied for each block.) Note that Math By Hand is a fully language arts integrated curriculum, with many stories, classic poems, limericks, and tongue twisters provided. Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of knowledge as a worthy goal. Tune in tomorrow for more Common Core, along with its ambient, Waldorf/Math By Hand counterpart.

Grade 2 / Block 1 / Morning Circle II

1) Choose 1-2 classic poems from the Binder, pages 85-92 and teach/learn them by heart.

2) Recite and/or sing (find the tunes online if you need to) 1-2 rhymes/songs from the Binder, pages 96-106.

3) Practice 4 Processes equations using the Color Cubes to accentuate the answers: tossing them back and forth, passing them around the circle, or switching hands, front and back.

4) Review 3’s up to 36, by saying them while walking in a circle.

5) Count by 4’s up to 48, using the 2’s as the in-between numbers, walking in a circle. Tiptoe and whisper the 2’s while marching and speaking the 4’s. (This is an introductionto the 4’s, and the 2’s as the in-between numbers will be dropped later on.)

6) Choose a number of Tongue Twisters and say them till smooth, the more the merrier!

Tags:

Day 125

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post will feature a Common Core Grade 2 Standard listed in blue, followed by its ambient counterpart as practiced by Waldorf Education and Math By Hand.

Operations and Algebraic Thinking 2.OA

1. Use addition and subtraction within 100 to solve one- and two-step word problems involving situations of adding to, taking from, putting together, taking apart, and comparing, with unknowns in all positions, e.g., by using drawings and equations with a symbol for the unknown number to represent the problem.

Before beginning here, I must say that the overall tone of these standards is that they have been hastily cobbled together, giving substance and solidity short shrift. It’s difficult to get a handle on them, to find a place from which to build. I don’t envy classroom teachers the daunting task of making sense of them, since they are so dry and devoid of any real context or substance. Common Core proponents say that the standards are merely scaffolding upon which to build a curriculum. But what has been built from them so far, the worksheets and textbooks, reflects their unworkability and difficulty. That said, onward.

As stated earlier, the 4 processes are learned and practiced side by side, all at once. Multiplication and division as well as addition and subtraction are reviewed in a horizontal format first, then switched to the vertical, single and double digit, with no regrouping as yet. Solving problems is only the half of it however. As in Grade 1, the 4 processes continue to be characterized and given personalities. Only with this depth of meaning and substance will math be learned correctly, effectively, and with joy. An abiding love of its beauty and deeper meaning is a missing element in our day and age, and must be regifted to our children.

Unknowns in all positions was practiced in Grade 1 with the counting gems and number strips, by moving the white square around on both sides of the equals sign. This can be continued, with either the horizontal or vertical format. Equations do switch back to the horizontal format in preparation for algebra and x as the unknown. But no rush on that. For now, make supplying the aforementioned substance and meaning a priority. Here is a story about how Saint Francis and subtraction share the same qualities, as it appears in the Grade 2 Daily Lesson Plans book.

Saint Francis / The Story of Minus

The characterizations of the 4 processes are essential to a deeper understanding and successful working with them. Read about the life of Saint Francis in the Grade 2 Form Drawing/Stories book, and keep that in mind as you tell this little story. It will help to show the quality of subtraction as that of both loss and unselfish giving.

Though Saint Francis was born quite rich and loved nothing more than having a good time with his friends, he was so moved by a poor, starving beggar in the street that he turned his silken pockets inside out, emptying them into the beggar’s hands. Very soon after that he fell very ill, and during this illness he painfully realized that he had to change his ways.

His friends laughed at him, but from then on Saint Francis could no longer keep anything for himself. He lost everything that was given to him because he gave it all away to those who were suffering and hungry. He often went hungry himself and became so poor that he had to live in a mountain cave. But Saint Frances glowed with another kind of wealth. Soon every person or creature he met wanted to be near him, and to follow in his ways.

Minus is like Saint Francis. Though it may seem Minus is poor and always losing everything, it could also be said that Minus gives away all it has. Loss is sad yes, but giving is joyful.

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of knowledge as a worthy goal. Tune in tomorrow for more Common Core and its ambient, Waldorf/Math By Hand counterpart.

Tags:

Day 124

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times. Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful.

Today’s blog features Part II of Cassie’s guest post. In light of the current trend toward more technology in the classroom and less direct teaching, less art, less movement, less of all that after all, makes us human, should we not reassess the value of the hand-made, human, teacher to student connection? Every teacher every one of us has valued in our lives, who in fact helped shape our very lives, had taught us on a human scale, touching the heart of every student in his or her care. This is doubly true of parents who choose to teach their children at home. Please read Cassie’s words with all of this in mind. And remember that knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of knowledge as a worthy goal.

Philosophy of Education – Part II

Cassie Lipowitz

Ph.D. Student, Graduate Theological Union

Lecturer, Religious Studies, Notre Dame de Namur University

Professor Davidson’s story (to read the story, see part I of this blog, posted yesterday) beautifully illustrates a paraphrased saying by educator Rudolph Steiner, that “To teach is to stand in the rain without an umbrella.”[i]In other words, to truly teach, one must become vulnerable, and learn to live in that space of vulnerability. It is in this space of vulnerability where teacher, students, and subject matter meet.

Parker J. Palmer, an educator and Quaker, insightfully articulates the interplay between these three—teacher, students, and subject—in his book The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life. Palmer emphasizes the extent to which a teacher’s “inwardness” or the condition of his or her soul, impacts the classroom. As a result, he writes, it is vital and imperative that as teachers we must come to intimately know ourselves, in addition to knowing our subject and our students:

Teaching, like any truly human activity, emerges from one’s inwardness, for better or worse. As I teach, I project the condition of my soul onto my students, my subject, and our way of being together. The entanglements I experience in the classroom are often no more or less than the convolutions of my inner life. Viewed from this angle, teaching holds a mirror to the soul. If I am willing to look in that mirror and not run from what I see, I have a chance to gain self-knowledge—and knowing myself is as crucial to good teaching asknowing my students and my subject.[ii]

As Parker goes on to argue, self-knowledge is perhaps the foundation of this three-part equation

…knowing my students and my subject depends heavily on self-knowledge. When I do not know myself, I cannot know who my students are. I will see them through a glass darkly, in the shadows of my unexamined life—and when I cannot see them clearly, I cannot teach them well. When I do not know myself, I cannot know my subject—not at the deepest levels of embodied, personal meaning. I will know it only abstractly, from a distance, a congeries of concepts as far removed from the world as I am from personal truth.

The work required to “know thyself” is neither selfish nor narcissistic. Whatever self-knowledge we attain as teachers will serve our students and our scholarship well. Good teaching requires self-knowledge: it is a secret hidden in plain sight.[iii]

And yet, in today’s educational milieu, it seems that many teachers have forgotten this vital aspect, or have simply found it too daunting and difficult to integrate such approaches while teaching in a system that stresses “hard results” (student learning outcomes geared more towards the sciences than humanities and liberal studies) and that “teaches to the test.” Likewise, many students do not seem to possess the tools to make what they learn relevant to their own lives. As a result, both teaching and learning suffer. As bell hooks asserts in her book, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom, “There is a serious crisis in education. Students often do not want to learn and teachers do not want to teach.”[iv] Rather than fostering true learning, it seems that far too many classrooms become information storehouses, in which teachers act as information siphons, with students falling into the role of passive learners. In such an environment, it is far too easy for students to slip through the cracks, or get by without learning much of anything. And yet, in spite of this crisis, “The classroom remains the most radical space of possibility in the academy.”[v]

As an antidote to the corrupt banking system of education, hooks proposes an “engaged pedagogy.” Engaged pedagogy emphasizes well-being, which means that “teachers must be actively committed to a process of self-actualization that promotes their own well-being if they are to teach in a manner that empowers students.”[vi]In such a pedagogy, education is envisioned as a libratory practice, in which teachers and students experience freedom through teaching and learning. hooks argues that

That learning process comes easiest to those of us who teach who also believe that there is an aspect of our vocation that is sacred; who believe that our work is not merely to share information but to share in the intellectual and spiritual growth of our students. To teach in a manner that respects and cares for the souls of our students is essential if we are to provide the necessary conditions where learning can most deeply and intimately begin.[vii]

Like hooks, I was disillusioned by many of my learning experiences during my first few years in college. I had expected to find highly intelligent and self-aware individuals—professors who would not only have access to information, but who would also understand how to apply it in the “real world.” Instead, I found myself continually disappointed by professors, who, though they lectured on fascinating material in the Humanities, and raised interesting questions in Philosophy, seemed for the most part incapable of bringing the subject material to life, and practicing what hooks terms “engaged pedagogy.” In addition, some of my professors seemed afraid to invite discussion (perhaps they feared the discussion might bring up uncomfortable issues, or provoke heated responses from students). In fact, I came to recognize a pattern that seemed to perpetuate in several of the classes I attended: whenever the discussion seemed poised to move in an intriguing direction (often prompted by a student’s question) the professor would almost invariably shut it down and move on to the next lecture slide, the next information bit. Sometimes, another student would immediately raise a similar question, or directly invoke the first students’ question, clearly indicating that this idea had sparked interest. More often than not, unfortunately, the professor would dismiss the second question as well, citing the need to “stick with the lecture and not fall behind schedule.”

In these moments, I found myself frustrated and sad—disappointed that once again, we had missed out on something that seemed to move beyond information and pre-determined structures—something that would have integrated the students fully into the conversation because it was an issue that truly engaged them, about which they expressed a passionate interest. The sense of frustration and the feeling that “there could be something more” has remained with me through my years in higher education. As I have transitioned into the role of teacher in the last few years, I have gained a new appreciation for the difficulty of balancing pre-planned lecture material with student-focused interests. Though I have more sympathy and understanding now for my professors who remained intent to “stay on task” (after all, stepping into the unknown can be frightening, as no one knows for sure where the conversation will lead!) I still maintain that student-directed learning (illustrated by the above story from Professor Davidson) is more effective, in certain ways, than any pre-fabricated lecture I could provide. This is perhaps because such discussions are “organic”, responding to the requirements and conditions of the moment.

As a humorous illustration of the way in which a lecture may fail to meet the needs to moment, I can relate a summarized version of a story from Book I of Rumi’s Masnavi: in the story, a deaf man learns from a wise man that his neighbor is sick. The deaf man, thinking that he will do good by paying a visit to his sick neighbor, but knowing he will not be able to properly hear what the sick man tells him, prepares in his head what he will say and how the sick man will respond. For example, he assumes that when he asks after the sick neighbor’s health, the man will reply with something along the lines of “I am fine,” and so he plans to respond with an exclamation of “thank God!” Next he decides he will ask the man what he has had to drink, and he assumes the man will answer with a positive response—such as sherbat or broth. Based on this, the deaf man thinks, he should respond with the exclamation, “I wish you health!” and then “Which doctor is treating you?” The deaf man surmises the sick man will answer such-and-such a doctor (presumably of reputable practice) upon which the deaf man plans to assure the sick neighbor of the physician’s deft skill, and that the sick man is now in excellent hands. Having preplanned this dialogue in his head, he goes to visit his neighbor. Of course, things do not go according to his plan, for his sick neighbor’s answers do not accord in the slightest with the deaf man’s assumed responses. When he ask the man how he is, the sick man essentially tells him he is on death’s doorstep, to which the deaf man gives his preplanned response, “Thank God!” This offends the sick man, and his anger only grows as the dialogue continues: in answer to the question of what he has had to drink, the sick man replies “poison,” and the deaf man says, “May it bring health!” When questioned about which doctor is treating him, the sick man tells him that Azrael[viii] is treating him. The deaf man then reassures the sick man that “His foot is blessed”—in other words, he is a reputable physician. Understandably, the sick man feels angry, betrayed, and hurt, and tells the deaf man to leave him alone.

In applying this story to the learning environment, we can make the following analogies: the deaf man may be seen to represent a teacher who, though well-intentioned, does not have the ability to truly know the needs of his students (“deafness” equals the inability or unwillingness to carefully listen, understand, and respectfully and articulately respond). Knowing this about himself, the deaf man decides he will preplan not only what hehimself will say, but also the sick man’s responses. This “preplanning” may represent a prewritten lecture, which the teacher sticks to in spite of whether it promotes true learning or not. The sick man, in this story, may represent the students, where sickness equates to a certain “lack” of knowledge, while the prospect of health represents learning, or gaining knowledge. Just as, in the Islamic tradition, it is considered a religious act to visit one’s sick friends and relatives, so too, the vocation of the teacher is, as bell hooks asserts, in some sense itself a sacred vocation and responsibility. While the deaf man has the best of intentions, he does not have the capacity or desire to truly listen, and thus only angers the sick neighbor. This anger can be equated to the disillusionment students may feel when they realize the sort of learning that happens in some classrooms is not genuine—or not all it could potentially be. In my experience, when students sense the instructor is not truly listening to them, they simply shut down, and essentially fall into a mindset of “get the grade and get out.” It is not fair, of course, to place the burden or blame entirely on the teacher’s shoulders—the problem is systemic and far too complex to fully explore in the present work. However, I would argue, along with bell hooks, that too often in college classrooms, we see “students…[who] do not want to learn and teachers [who] do not want to teach.”[ix] This frequently translates to teachers who do not truly listen to their students, and students who do not listen to each other and only selectively listen to the teacher for the information that “will be on the test.”

In spite of the above criticisms, this is not to say that lecture and memorization don’t play a role in higher education, for they certainly do. Rather, as Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger, and Tarule point out in their feminist pedagogical study, Women’s Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice, and Mind, “received knowledge”—that is, knowledge or information one acquires through “listening to the voices of others,” and especially those perceived as authorities—is only one of the ways of knowing, and co-exists alongside other kinds of knowledge, such as subjective knowledge, procedural knowledge, and constructed knowledge.[x]Unlike received knowledge, which depends upon external authority only, subjective knowledge arises from within—from the learner’s own experience—as part of what Belenky, et al identify as “intuitive” knowledge. While both received knowledge and subjective knowledge are dualistic in nature, insofar as they assume there is only one means for arriving at a correct answer to the given issue or problem[xi], procedural and constructed knowledge allow for multiple means of arriving at an answer or solution. According to the authors, procedural knowledge consists of two subdivisions: separate knowing and connected knowing. For separate knowers, the primary method of learning consists in critical thinking and testing: “Presented with a proposition, separate knowers immediately look for something wrong—a loophole, a factual error, a logical contradiction, the omission of contrary evidence.”[xii] Connected knowers, on the other hand, seek to understand, and even enter into—as fully as possible—the worldview of others: “Connected knowers know that they can only approximate other peoples’ experiences and so can gain only limited access to their knowledge. But insofar as possible, they must act as connected rather than separate selves, seeing the other not in their own terms but in the other’s terms.”[xiii] While separate knowers and connected knowers have different approaches, both “…learn to get out from behind their own eyes and use a different lens, in one case the lens of discipline, in the other the lens of another person.”[xiv] Finally, constructed knowledge integrates, in a sense, all of the other approaches or “voices”—it incorporates “reason, and intuition, and the expertise of others.”[xv] Ideally, a great teacher, acting as a metaphorical “midwife”, will be able to help the student “birth” the constructed knower within him or herself.

Fortunately, I had the honor of attending courses with a few professors who, indeed, had the capacity to act as “midwives” in the sense described above. Like Norman Davidson, they allowed themselves to be vulnerable enough to let learning evolve in the moment; further, they also intuitively understood how to guide their students (rather than simply feeding them the answers) so that students themselves would “learn how to learn.” It wasn’t that these teachers were “lazy” in terms of preparation or in structuring their classes—rather, they saw new possibilities for what the classroom could be. Somehow, almost miraculously (though undoubtedly it required much hard work on both personal and professional levels) these professors found their way into an approach that allowed them to meet the needs of their students in the moment. In short, they had gained the ability speak about—or even embody—the subject matter in a way that ignited the students’ interest and passion for learning, and thus bring together the three core components of the classroom: teacher, subject, and students. Teachers such as the ones described above are able to create an environment wherein, in the words of professors Susan E. Hill, Linda May Fitzgerald, Joel Haack, and Scharron Clayton, students “…begin to question the structures of social reality and their assumptions about it. Once this occurs, the professor is no longer seen as the beginning or end of students’ learning, but rather as a catalyst for their continued reflection and questioning of the phenomena around them.”[xvi]

In contemplating my own philosophy of education in the context of the above quote, a particular story comes to mind, which I first heard over 10 years ago in Dr. Amir Sabzevary’s Introduction to Philosophy class at Sierra College. As I recall, we were discussing Jean Paul Sartre that day, and, in particular, the concept of “bad faith.” To illustrate the ideas we were discussing, Professor Sabzevary told the following story:

There was once a man who had spent his entire life working for a master architect. He toiled for many years and grew skillful in his trade, building many beautiful houses. However, the houses he built were always for others; never for himself. Finally, after a lifetime of work, he said to the master architect, “I’m tired; my body and soul are weary. It’s time I retire.” But the master architect said, “just build one more house–just one more, and then I promise I won’t ask you for anything more.” The man reluctantly agreed, but his heart wasn’t in it anymore. And because he was tired, when he went to the lumber store, he selected the cheapest, flimsiest materials; and when he built the house, he did not use as many supports as he should and was generally lax in the construction. Finally, when he finished, he went to the master architect, and, dropping the keys to the house in his boss’ hand, said, “The house is finished. I wish to retire now.” And the master architect smiled and gave the keys back to the man, saying, “The house you have just built is my retirement gift to you.” Only then did it occur to the man how poor was the house’s foundation and construction, and by then it was too late…[xvii]

In this story, the man builds houses his entire life, and, under the guidance of a master architect, even becomes competent at his craft—yet the houses he builds are never “his own.” In the same way, a student may study for countless years, even acquiring certain skills, but unless he or she learns to integrate the information and make it relevant within the context of his or her own life experience, he or she will eventually burn out, become discouraged, or simply arrive at the conclusion that there is no point to such efforts. In this case, he or she will be left to live in a flimsy “house”—a house that is strung together solely by means of other people’s ideas, and constructed without any self-insight or self-knowledge. One point of this story, as I see it, is that we are each responsible for our own education, and that, in the end, the “house” we choose to build is the house we will live in for the remainder of our lives. If, with a combination of skill, creativity, self-insight, and guidance from a master teacher (who is, him or herself, always also a learner!), we are able to construct a solid, spacious, and aesthetic house, we have accomplished more than most.

[i] Rudolph Steiner, Study of Man: General Education Course (East Sussex: Rudolph Steiner Press, 2004), 24.

[ii] Parker J. Palmer, The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1998), 2.

[iii] Ibid., 2-3.

[iv] bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (New York: Routledge, 1994), 12.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid., 15.

[vii] Ibid., 13.

[viii] In the Islamic tradition, Azrael is the angel of death who comes to take those who are on the brink of death.

[ix] bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (New York: Routledge, 1994), 12.

[x] Mary Field Belenky et al., Women’s Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice, and Mind (New York: Basic Books, 1986) 35-133.

[xi] According to these authors, “received knowers” assume the correct answer exists outside themselves only, while “subjective knowers” assume that instinctual or intuitive knowledge is more reliable than any external authority, and initially tend to reject “outside” answers, especially when those answers contradict what their own instincts tell them.

[xii] Belenky et al., Women’s Ways of Knowing, 104.

[xiii] Ibid., 113.

[xiv] Ibid., 115.

[xv] Ibid., 133.

[xvi] Susan E. Hill, et al., “Transgressions: Teaching According to ‘bell hooks.’” The Nea Higher Education Journal,

p. 45

[xvii] Amir Sabzevary, lecture, Sierra College, Rocklin, CA, February 2003.

Tags:

Day 123

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times. Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful.

A couple days away from Grade 2, to talk about teachers and students, with a visitor who touches on this magical relationship. This guest blog was written by my daughter, Cassie Lipowitz. Cassie teaches World Religions, Islam, and Women’s Spirituality at Notre Dame de Namur University, in Belmont, CA, and is midway through a doctoral program in Berkeley, CA. The writing below is the part I of her Philosophy of Education. Part II of that piece will be posted on this blog tomorrow.

Philosophy of Education – Part I

When I was in first grade, my mother and I spent our weekdays for the entirety of the school year living in a tiny attic apartment a few hours away from our home. This was so that both of us could attend the nearest Waldorf School—I, as a member of the first grade class, and my mother as a teacher trainee. She had recently discovered Waldorf education and, disillusioned with the public school system, she decided not only to provide an alternative education for me, but to become a Waldorf teacher herself. Many years later, when I first started thinking about entering the teaching profession, she told me some memorable stories from her time in teacher training. One story, in particular, has stuck with me. This story was related to my mother by one of her best teachers in the Waldorf trainee program, a native of Scotland named Norman Davidson. This version of Professor Davidson’s story, entitled “A Lesson in the Dark,” appeared in print in the Summer-Autumn 1978 edition of the journal Child and Man: A Journal for Contemporary Education:

I walked across the school playground towards the classroom thinking about Ernest Hemingway. It was a fresh, sunny day in late autumn, but inwardly I was transporting myself to the seas around Cuba where big fish are caught, and to the sun drenched arenas of Spain where the ritual of killing the bull is enacted. In both, the human being relates to nature in a strange and contradictory way—predatory yet awe filled in the presence of death; hunting for challenge, yet really hunting after oneself. Similar contradictions, translated into social relationships must surely lie, I thought, somewhere in the feeling life of many a young teenager, and wait to be solved.

Many things go through the mind of a teacher on his way to the classroom, especially if he is new to the school as I was. Had I prepared the lesson properly? Would it be received well? Would it relate to the young people before me? I was sure that Hemingway related sooner or later to the class of thirty or so boys and girls around the age of fifteen towards whom I now walked in this British Waldorf school. But nevertheless the night before I had wondered about presenting Hemingway just at that time in these literature and English lessons. I entered the school and walked down the corridor. It was too late now to change.

When I arrived outside the door it was shut. On opening it there was a double shock. Firstly, I stepped from a bright, sunny atmosphere into complete darkness. The window blinds were tightly down, and I could hardly see my way to the teacher’s desk. Secondly, although I could sense a lot of people in my presence, there was hardly any sound. I had to think quickly. This was not a particularly easy class in some ways. A few days before, a group of them had sat in the playground in a circle after the school bell, protesting against something. So now they were testing me. Instinctively I knew why they were doing it. “Who are you?” they were saying. “Throw away your book and your briefcase. What are you going to do now?”

I walked towards the window where light showed, but quick hands closed up the chink. The first impulse was to admonish them strongly for being so silly, switch on the light and demand that they immediately pull up the blinds. After all, my lesson was being infringed, and time was being wasted. But the hush in the class made me hesitate. I could hear them breathing and listening and occasionally whispering— all thirty of them. The air was full of expectancy. I stopped myself from reacting as a conventional ‘teacher’ and wondered what I could do as an unconventional one.

I felt my way round to the front of the teacher’s desk and stood staring into darkness. Boy, could these children wreck a lesson! So I thought that the best thing would be to say the first meaningful thing that came to me and take it from there. I heard myself say, “For today’s lesson you are going to have to use somewhat more imagination than usual.” (There was a ripple of conceding laughter. Well, that was something). “You will have to listen to my voice today without the help of seeing my movements, gestures and facial expressions. A kind of reversed mime. So you’ll have to listen more carefully. (Sounds of “Shh.”)

“When you don’t see someone’s face who is talking, you can more easily be led astray as to shades of meaning. I might, for instance, be saying all this to you in a serious voice, but without you knowing it, I could be grinning like an ape.” (I grimaced crazily into the darkness and, sensing it, the class rippled with laughter again, then fell silent, waiting.)

I was at sea, but it was less and less Hemingway’s Caribbean. The big fish and the bulls were receding into the dim distances in my mind. I was brought intensely to the here and now of thirty young people who needed something and were teaching me how to teach it. So I plunged into this new sea and into the uncanny experience of having to imagine the young people to whom I was talking, even though I knew them. Gradually, the lesson was drawn out of me. The following are paraphrases of parts of it.

“You’ll have to see today with your thoughts. For someone like the great philosopher Plato, to think was to see. Even in English we say ‘I see’ when we understand something with our thoughts. Some people can see with their thoughts very well. Being without sight is a help. During the last war there was a blind resistance fighter in the French underground movement to whom all recruits for the resistance were brought. He could tell by the tone of the person’s voice in answer to questions whether he was a spy or not. It is also known that blind people dream in pictures…

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of knowledge as a worthy goal.

Tags:

Day 122

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post features a block plan for the Grade 2 year.

Math By Hand, a Waldorf-inspired curriculum, is set up for teaching in blocks. In Grade 2 there are four math blocks that are divided into 15 days each. These can be adjusted if needed, and it is also possible to convert the block content into full-year daily lessons.

The advantages to teaching in blocks are many. Yearly planning is easier, and because the lessons are taught in 1 – 2 hour blocks in the morning, teacher / student focus is greater. Afternoons are freed up for art, handwork, games, field trips, family time, etc. Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of knowledge as a worthy goal.

September Legends / Lower Case Letters

October Math Block 1: Times Tables Chart / Tables and Fables

November Fables / Writing and Reading

December Nature Studies / Legends

January Math Block 2: 4 Processes Review / Place Value

February Legends and Fables / Writing and Reading

March Math Block 3: Times Tables / Tricks and Patterns

April Nature Studies / Fables

May Math Block 4: 4 Processes Practice with Regrouping

June Class Play

Tags:

Day 121

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post features the Common Core Grade 2 overview in blue, followed by its ambient counterpart as practiced by Waldorf Education and Math By Hand.

Operations and Algebraic Thinking

Represent and solve problems involving addition and subtraction.

Add and subtract within 20.

Work with equal groups of objects to gain foundations for multiplication.

The 4 processes are taught and learned side by side from the very beginning. Equations are written horizontally at first in Grade 1, as number sentences. Single digits totaling no more than 20 are worked with in addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. After briefly reviewing the Grade 1 content at the beginning of Grade 2, the horizontal format is changed to vertical, using double digits with no regrouping, in all 4 processes up to 100. No need to build foundations for multiplication as it’s been included from the beginning.

Number and Operations in Base Ten

Understand place value.

Use place value understanding and properties of operations to add and subtract.

In Grade 2, place value is taught in the second of four math blocks, using hands-on materials and manipulatives. Place value understanding is used primarily in regrouping with addition and subtraction. Regrouping is also used with short multiplication and division until mid-Grade 3 when their long versions are taught.

Measurement and Data

Measure and estimate lengths in standard units.

Relate addition and subtraction to length.

Work with time and money.

As stated in an earlier post, time and measurement wait until Grade 3 in both the Waldorf and Math By Hand systems. Though must children will be somewhat familiar with both, it’s best to hold off formal instruction until age 9, when the optimal developmental readiness allows maximum retention and understanding. However, foundational activities in both areas may be both doable and helpful.

Geometry

Reason with shapes and their attributes.

As has been previously shown, form drawing is more than adequate to address this standard.

Teaching in blocks is a wonderfully efficient way to cover all academics, while having the afternoons free for the fun, creative stuff. Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of knowledge as a worthy goal. Tune in tomorrow for a suggested Grade 2 full-year block plan.

Tags:

Day 120

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Welcome to Grade 2! Today’s post will feature excerpts from the introduction to Grade 2 in the Math By Hand binder.

The Grade 2 “mood” is one of contrasts. There’s a settling in to the new world of challenges and learning begun in Grade 1, accompanied by a certain restlessness. As all boundaries are tested, there’s a desire to take on more, often expressed as a somewhat overly confident rambunctiousness.

This quality is reflected in the Aesop’s Fables’ brashly bold animal characters, because they repeatedly test any and all boundaries. The fables’ moral lessons are juxtaposed against the legends that feature the lives and deeds of saints and heroes.

In Grade 1, learning to read though writing the upper case letters built a solid foundation that continues this year, as the lower case letters are added. Their 3-part structure (on the line, above and below it) mirrors a math content that’s also becoming increasingly complex.

Since regrouping can be a challenging concept, it’s taught with big, colorful hands-on aids and tools. Patterns and form drawing are helpful as well, since finding patterns in math fosters interest and creativity, as well as providing reinforcement of knowledge and skills.

Familiar games that are also math-friendly integrate learning with highly motivational fun. Movement and rhythmic counting continue, and times tables remain an important focus, since they are so essential to understanding fractions, decimals, measurement, and even algebra!

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. Tune in again tomorrow for more Grade 2 . . .

Tags:

Day 119

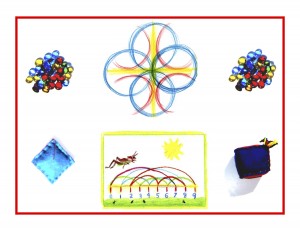

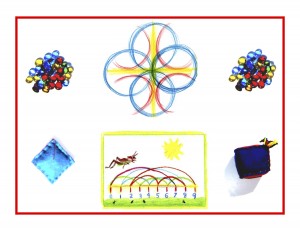

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Leaving Grade 1 today, and moving on to Grade 2 tomorrow, a magical story from France that correlates to the number 3: The Prince in the Black Scarf, will round out the Grade 1 posts. Look below for drawings and captions to accompany the story, noticing how the triangle relates to both the story and the number 3.

Once upon a time there lived a very wealthy King of France. He was very wise and was loved by all his people. He had a beautiful Queen who gave him a son. The Prince grew into a handsome youth. He soon reached his seventeenth year. But then the Prince fell into bad company, drinking and gambling. The people of the Kingdom feared he would never make a good King when his father died. “Your son must be taught a lesson,” said the elders of the city to the King. The first time they complained, the King ordered the Prince to be given a hundred lashes, but he soon fell back into his old ways.. The second time they complained, he was whipped and sent to prison for one year. Again he returned to his bad friends. The third time the elders complained the King promised that his son would be executed. The elders tried to calm him, but the King was deter-mined. The Queen ran to find the Prince first. “Here is a bag of gold, your sword, and your horse. Go out into the world and find your true path. I do not want to see you again until you do.” The following morning the Queen told the King what she had done. The King was not angry but he said that if his son returned, he would send him to the gallows as he had promised. Meanwhile the Prince had ridden far across the Kingdom. He stopped to spend the night in a clearing in a forest. As he sat, he saw a hawk swoop down and catch a mouse. Then a vixen dashed out of the bushes and caught the hawk. Suddenly an arrow flew through the air, killing the vixen. As the huntsman rode up and leaned out of the saddle to pick up the fox, the string on his bow snapped. It flicked against his horse and made him bolt. The hunter was unseated but his foot was caught in the stirrup dragging him along. This all happened so quickly, the Prince did not have time to move. He thought carefully about what he had seen. He realized that one bad deed could only lead to another and that his father had been right to punish him. The Prince decided to change his ways. The following morning he sold his horse and gave all his money to the poor. He kept his sword and he put a tattered cloak over his fine clothes and put a black scarf over his head with holes for his eyes, nose, and mouth. After walking for seven weeks, the Prince found himself by a hut in the middle of a forest. A hermit lived in the hut. “Welcome, Prince of France,” he said to the Prince. “How do you know who I am?” asked the surprised Prince. “I know who you are and why you are here,” said the hermit. “Now leave me your sword, your fine clothes, and your scarf. Put on these old clothes, go to the end of this path and find work with the farmer there.” After seven days’ walk the Prince came to a farm. The farmer there took him on as a swineherd. He took the pigs every day to a field by the sea. One day, while he was there with the pigs, he heard a scream come from the edge of the forest, and he saw an old woman. Her goat was being dragged away by a wolf. The good Prince clubbed the wolf with his crook so that it dropped the goat and ran. “Thank you, Prince,” said the old woman. “When you need help, come to this hollow tree, knock three times and I shall come to your aid.” Then, she and the goat disap-peared in a mist. The Prince returned to the farm that evening to find the farmer with a troubled look on his face. The Prince asked him what was wrong. “A giant is roaming the French countryside. Wherever he goes the countryside dries up. He is turning France into a wasteland.” “Has no one tried to kill him?” asked the Prince. “The have tried, but they have all failed. The giant cannot be destroyed.” The next day, as the Prince was driving the pigs to pasture he stopped by the hollow tree and knocked three times. At his third knock, a beautiful girl appeared. “Good day, Prince,” she said. “I know why you are here. Listen carefully. If you wish to slay the giant you must strike his diamond eye with your sword. Fetch your clothes, sword, and black scarf and follow the midday sun for seven days until you reach a dry plain. Hide inside the ruined castle there and wait. The giant will come as night falls. He will stretch out across the plain and go to sleep. On the stroke of midnight you must strike him with your sword.” With that the girl disappeared. The swineherd said goodbye to the farmer and returned to the hermit’s hut where he collected his belongings. After seven days’ walk, he reached the ruined castle on the plain. As night fell, the giant returned to the plain and lay down to sleep. At the stroke of midnight, the Prince came out of his hiding place and struck the giant in his diamond eye. The giant sighed and then disappeared. All that was left was the diamond eye. The Prince picked up the diamond and, still wearing his black scarf, he took it to the French court. He saw the Queen looking out of the window but she did not see him. “I bring you the diamond eye of the giant, sire,” said the Prince to the King, “as proof of the giant’s death.” “Thank you, man in the black scarf,” said the King. I will reward you with one hun-dred thousand gold coins for slaying the giant.” I do not fight for reward, but for honor,” said the Prince in the black scarf. “If you do not need the money, then give it to the poor.” “I see you are noble as well as brave,” said the King. “Show me your face.” I cannot, sire, replied the Prince. “My father wishes never to see my face again, so I cannot uncover it, even for you.” “Your father should be proud of you,” said the King. My own son is a failure.” “I know him well, sire,” said the Prince. “He has changed a great deal.” “I find that hard to believe,” said the King. “If I lay eyes on him I shall send him straight to the gallows.” The Prince left the King, but he waved once to the Queen. He returned to the hermit at the edge of the forest. “Welcome, Prince,” said the hermit. “How did you get on?” “I killed the giant, and took his diamond eye to my father, the King. But he will not have me back,” said the Prince. “That is because you have not been fully tested,” said the hermit. “Return to your work at the farm.” The Prince left his belongings with the hermit and returned to the farmer and again became a swineherd. He drove the pigs to the meadow by the sea every day. Several weeks passed, and one day as he was sitting watching the pigs, a golden bird settled in the branch above his head. “Good day, Prince,” said the golden bird. “I am the golden bird who will live forever. Every hun-dred years I must have a drink of human blood or I shall die. Good Prince, will you help me, as today it is one hundred years since I last drank?” “Of course, I will help you,” said the Prince. “Fly down and drink.” So saying, the Prince cut his arm and the bird flew down and drank. “Good Prince, when you need my help, come to these woods and clap three times,” said the bird, when it had finished drinking. It then flew away. At the end of the day the Prince returned to the farm. There he found the farmer looking very sad. He asked him what was wrong. “A terrible dragon has come to the land. It is catching people and animals and eating them. Nothing can stop it.” “Hasn’t the King sent soldiers against it?” asked the Prince. “Indeed, but it is too big and strong. It has eaten many of them.” The next morning the Prince drove the pigs to the meadow, but he stopped by the woods and clapped his hands three times. “I know why you are here, Prince,” said the Golden Bird as it appeared on the branch. “Take this feather and put it in your mouth and you will change into a bird. Spit it out and you will change back. The dragon you seek can only be killed by stabbing it through the heart. Follow the midnight moon for seven nights until you reach some mountains. The dragon’s cave is there. You must fly into his open mouth and strike from the inside. Now, goodbye.” The Prince once again said goodbye to the farmer and returned to the hermit where he put on his fine clothes, his sword, and his black scarf. After seven nights of following the midnight moon, he reached the mountains. As night fell, the dragon with a golden crown on its head returned to its cave. It settled itself down to sleep. As its mouth opened the Prince changed into a bird and flew in. He flew down toward the dragon’s heart. There he spat out the feather and the Prince then stabbed the dragon’s heart with his sword. The dragon sighed and disappeared and all that remained was the gold crown. The Prince picked up the golden crown and took it at once to the French court. As he walked in, the Prince saw the Queen by the window. She turned and looked at him. “I have killed the dragon,” said the Prince as he gave his father the dragon’s crown. “Once again, you have done my Kingdom a great service,” said the King. I shall give you two hundred thousand gold coins as a reward.” If you do not need the money, give it to the poor,” said the Prince. I seek honor rather than reward.” “You are still a noble man,” said the King. “Let me see your face.” “Ah, no, your majesty,” said the Prince. “As I said before, I cannot show my face.” “Your father should be proud to have you for a son,” said the King. “My own son is a failure.” “I know him and he has changed,” said the Prince. “Can I not tell him that you would like to see him again?” “No,” cried the King. “If I see him he goes to the gallows.” The Prince turned and left, but he waved to the Queen. He returned to the hermit. “How did you fare?” “I killed the dragon and took its crown to my father, but he still will not have me back.” “That is because you have not been fully tested,” said the hermit. “Return to your work at the farm.” The Prince returned to the farm and again became the farmer’s swineherd. He drove the pigs to the pasture by the sea every day. One day he was sitting watching over the pigs, when a huge bird swooped down and came up with a large golden fish in its claws. The fish struggled to get free but the bird held on tight. So the swineherd leapt up and hit the bird with his crook so that it released the fish. The fish swam up to the Prince. “Thank you, Prince. When you need my help, you must throw three handfuls of sand into the sea, and I shall come.” Then the fish disappeared. The Prince returned to the farm in the evening with the pigs. When he entered the farmhouse, the farmer was looking very miserable indeed. “What’s wrong?” asked the Prince. “A terrible plague is sweeping across the country. The people are dying everywhere. They say that the King and Queen are ill with it.” “Is there no doctor who can help?” asked the Prince. Doc-tors have tried to find a cure, but even they are dying of it,” said the farmer. The next day the Prince said goodbye to the farmer. “I must go,” he said. He then went down to the sea and threw three hand-fuls of sand into the sea. As he threw the last handful the golden fish appeared. I know why you are here, Prince, and I will help you,” said the fish. “You must fetch the Golden Flower with the scent of balsam and plant it in the courtyard of the palace of the French King to rid the country of the plague. But the flower grows on an island in the middle of very rough seas. I will take you to it.” So saying, the fish took the Prince on his back and swam away from the shore across the sea. The seas were rough and stormy, but they finally reached the tiny island. “Go and collect the flower and I shall take you back to shore,” said the golden fish. The Prince leapt off and found the flower with the scent of balsam. He returned with it to the fish. The golden fish swam safely back through the mountainous waves and left the Prince on the beach near the hermit’s hut. Then the golden fish disappeared. The hermit came out of the hut with the Prince’s clothes, his sword, and the black scarf. “You will have to hurry. I have already saddled your horse,” said the hermit. The Prince put on his clothes and the black scarf and mounted the horse. He said farewell and galloped off to the French court. He was standing in the courtyard of the palace in no time. He dug a hole and planted the Golden Flower. Immediately the scent of balsam was everywhere. All the town and the Kingdom came to life again and the plague left the country. The Prince entered the palace. There he saw the Queen by the window. She saw the man in the black scarf and she jumped up. “Welcome, my son, I knew it was you.” She embraced her son fondly. Then the Queen and Prince hurried to the King’s room, where he lay in bed gravely ill. “Welcome, man in the black scarf,” said the King. “What brings you here?” “I have brought the Golden Flower with the scent of balsam to cure the kingdom of the plague.” “Thank you for this great service. I give to you my crown and my Kingdom, for I am old and my son is a failure who will never be King.” “I know him well and you do him an injustice,” said the Prince. “He is no more a failure than I am. He would dearly like to come back to you if you could forgive him.” “If he could be as good a son as you are, then I would forgive him,” said the King. “Then forgive him now,” cried the Prince as he pulled off the black scarf. Then the King recognized his son. He was overjoyed to see him. The old King ruled on and when he died the good Prince took over the reign of the Kingdom. Never was there so just or wise a King of France.

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. Tune in tomorrow for Grade 2!

Tags:

Day 117

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful.

Stories and art are at the heart of Waldorf education. Stories are found throughout the curriculum, from fairy tales in Grade 1 to the biographical and historical stories in the upper grades. A rhythm is employed when telling a story and then using it for the purpose of teaching a new concept or idea.

The new concept is cloaked in the lovely garment of the story, rather than being presented as bare fact. The story is told on day 1 and then retold by the child(ren) on day 2. The story is remembered in every detail, indicating how deeply it lives within. And as such, it very effectively communicates what is being taught through it.

On day 2, after the story is retold by the child(ren), it’s related to the lesson. For instance, a fairy tale featuring a King might be told for teaching the letter K. After the story is retold, the teacher could strike a pose as the King stepping forward and raising his arm in greeting to his subjects. When the child(ren) imitate(s) the King’s pose while saying the greeting, the feeling of the letter K is experienced as bodily movement.

Standing with a piece of blank, white paper taped to the board or a wall, the teacher uses the broad end of a yellow crayon to lightly block in the letter K, large on the page. It can then be dressed and crowned as the King! And the letter K can be drawn large, on the facing page.

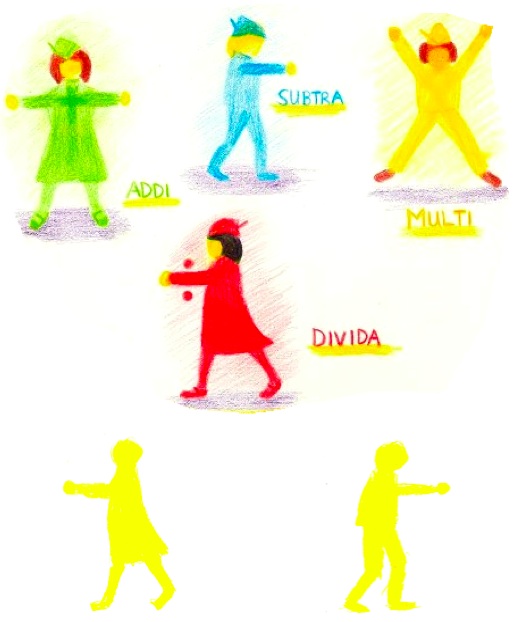

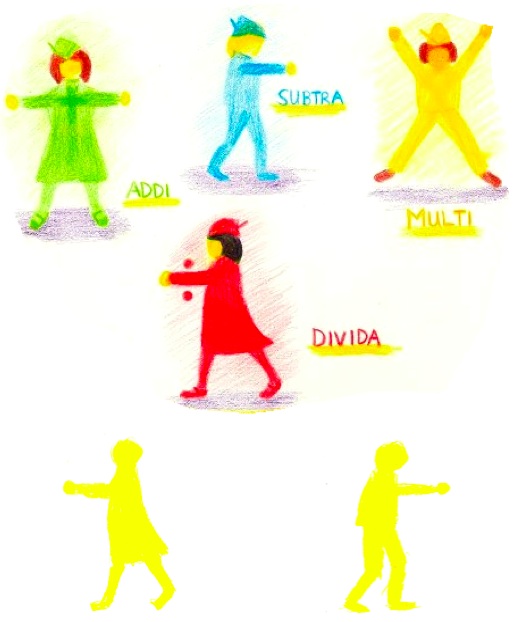

When drawing figures (like the 4 Processes characters shown below) block the figures in yellow then add details: clothing, hair, shoes, etc. Hands can simply be round balls as shown, and faces can be left blank (this allows the flexibility of being able to see the faces through lively, imaginative pictures). Notice how body language conveys the very different character of each one.

Consider that guiding the child(ren) in this way rather than leaving them free to do their own artwork is providing necessary instruction, rather than hindering freedom of expression. And always remember that knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. Tune in tomorrow for Addi’s, Subtra’s, Multi’s, and Divida’s special stories!

Tags: