Day 85

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Because the Common Core Grade 1 Math Standards address addition and subtraction exclusively, they will appear here later, in conjunction with the blocks that focus on the 4 processes. Earlier math blocks focus on meeting the numbers up close and personal through stories, movement, art, form drawing, and hands-on activities like making real numbers. The numbers should come together for calculation only after an in-depth introduction has established them as friendly and personable, so essential for circumventing math fears and phobias!

Only after a solid foundation has been built, with a thorough introduction and familiarity with the numbers themselves, where they came from, how they came to be, and how they relate to pictures and stories, should the numbers come together in calculation. There is no reason why all 4 processes should not be introduced together. If the calculations are kept simple (single digit and under 20) it’s immeasurably better to keep them together from the beginning. The following is an excerpt from the Math By Hand Grade 1 Binder.

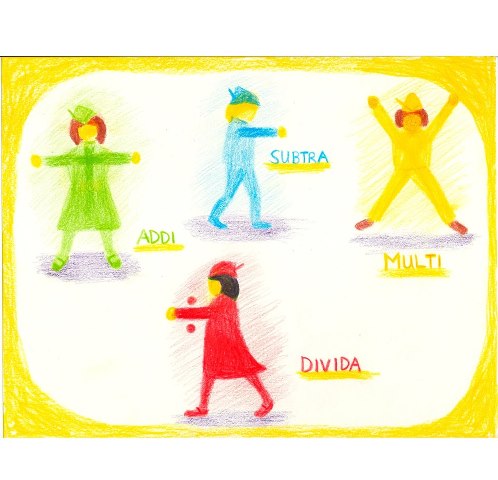

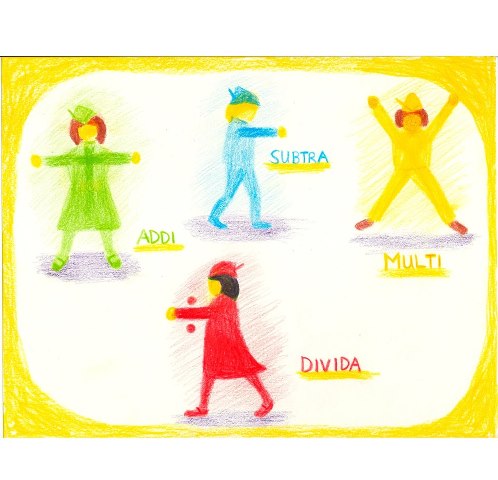

The next step then is to bring the numbers together, to form relationships and characterize their interactions. It’s most effective to introduce all 4 processes at the same time, while illustrating their qualities, differences, and similarities. They can then be featured in the context of stories, costumes, and plays. In this way, their respective traits are brought to life, as they are each and all personified in various lively interactions. Here are suggestions for personalities and characterizations:

ADDITION/PLUS could be acquisitive, plump, GREEN and growing.

SUBTRACTION/MINUS is sad, BLUE and always losing things.

MULTIPLICATION/TIMES is complex and busy, YELLOW and very happy to be so.

DIVISION/DIVIDE is decisive, RED and definite.

A little costuming and story creation is all that’s needed to convey the “mood” of each of the processes. This concept goes a bit beyond math, since it can also be seen as a window into aspects of personality and character.

This is a formative time for the child. When the Grade 1 academic material is brought as an integral part of life, it can carry more than the merely abstract concepts. If presented in the right way, all the lessons will point beyond their immediate purpose. In that light, the traits of the 4 processes can be a mirror, reflecting qualities that resonate on deeper levels.

Along with the qualities mentioned above, others can be added in a complementary way. For instance, PLUSmight be seen as industrious and persevering, as well as greedy and acquisitive, as she stays with the job to the very end, until it’s finished. One view of MINUS might be that he is sad and always losing things. But another aspect could be that he is generous and always giving things away. Likewise TIMES, besides being complex and busy, could also be said to be helpful, willing to take on more than his share. And DIVIDE, as decisive and definite as she is, may also be called upon to be an impartial judge, because of her fairness and accuracy.

Awareness of the child(ren)’s temperaments can be helpful. There are 4 temperaments in all, and we all have a bit of each one, with one or two that predominate. These are universal qualities or personality traits that tend to be more singularly individual at first. As the child matures, the dominant trait is often modified or balanced, blending with the others. When these qualities are mirrored back, as they can be with the 4 processes characterizations, it is helpful for the child, as it promotes an understanding tolerance of self and others.

Create plays and stories around the four personalities, enabling them to become knowably approachable. Give them names like the more formal ones listed below or choose familiar nicknames like those in the drawing at the bottom of this post. The characters and their respective colors should be a persistent theme. For example, have Addy or Plus appear with all addition problems. Same for Subtra/Minus, Multi/Times, and Divida/Divide.

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. Tune in tomorrow for examples of plays and stories used to introduce the 4 processes.

CHOLERIC . . . DIVISION . . . “DIVIDE” . . . RED

PHLEGMATIC . . . ADDITION . . . “PLUS” . . . GREEN

MELANCHOLIC . . . SUBTRACTION . . . “MINUS” . . . BLUE

SANGUINE . . . MULTIPLICATION . . . “TIMES” . . . YELLOW

Tags:

Day 84

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Because the Common Core Grade 1 Math Standards address addition and subtraction exclusively, they will appear here later, in conjunction with the blocks that focus on the 4 processes. Earlier math blocks focus on meeting the numbers up close and personal through stories, movement, art, form drawing, and hands-on activities like making real numbers. The numbers should come together for calculation only after an in-depth introduction has established them as friendly and personable, so essential for circumventing math fears and phobias!

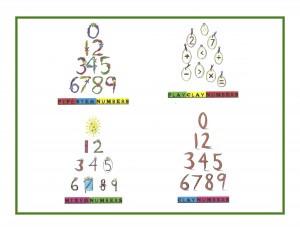

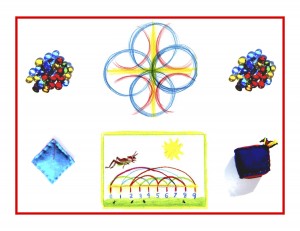

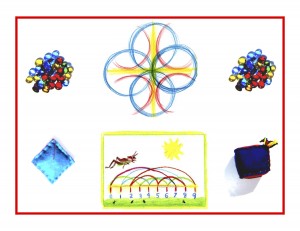

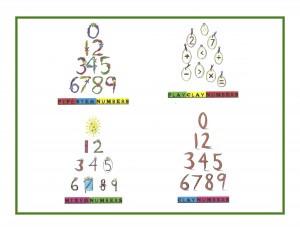

The second math block should focus on making real numbers. Why? Our base-ten, Arabic numeral system is simple to grasp; there are only 10 number forms to learn, 0-9. These numbers however, have little to no correlation to their visual appearance, as the Roman numerals do. Since they’re more abstract in that way, learning and writing them can be challenging. For this reason, sculpting or forming the numbers by hand can be very helpful.

The Math By Hand / Grade 1 / Kit 2 / Real Numbers contains materials and instructions for making three complete sets as shown below using pipe stems, clay, mixed materials, and play clay. The numbers are fun to make, help to insure correct formation, and allow an affinity for each one as it’s lovingly created by hand. In the Grade 1 Daily Lesson Plans book, the second math block (Real Numbers) focuses on one number a day, as the same number is made by hand using a variety of materials. These number sets and operations signs can be used later for learning and practice with the 4 processes.

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. Tune in tomorrow to find out why all 4 processes are taught at once in Grade 1.

Tags:

Day 83

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Because the Common Core Grade 1 Math Standards address addition and subtraction exclusively, they will appear here later, in conjunction with the blocks that focus on the 4 processes. Earlier math blocks focus on meeting the numbers up close and personal through stories, movement, art, form drawing, and hands-on activities like making real numbers. The numbers should come together for calculation only after an in-depth introduction has established them as friendly and personable, so essential for circumventing math fears and phobias!

The second math block should focus on making real numbers. Why? Our base-ten, Arabic numeral system is simple to grasp; there are only 10 number forms to learn, 0-9. These numbers however, have little to no correlation to their visual appearance, as the Roman numerals do. Since they’re more abstract in that way, learning and writing them can be challenging. For this reason, sculpting or forming the numbers by hand can be very helpful, and there are many ways to do this.

One fun way is to construct sandpaper numbers and use them both to learn the number forms and for 4 processes practice later on.

1) Trace the numbers 0 – 9 onto heavy paper or cardstock, using large (at least 4 – 5” inches tall) number stencils, or draw them freehand.

2) Carefully cut each one out, then flip them right-side up and backwards.

3) Trace the reversed numbers onto the back of medium grain sandpaper sheets and cut them out.

4) Center and glue each number onto a paper plate (Chinet is a good brand to use).

5) Trim the outside edge off the plate, so it resembles a frisbee.

6) Mark the center top of the plate to indicate correct placement. You could also punch a hole and thread a yarn or string loop through, as shown in the picture below.

This is similar to a Montessori technique used for tactilely experiencing number and letter forms. Make two or three of each number and use them for 4 processes practice! (You may want to add the sandpaper five operations signs for this as well.)

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. More real numbers tomorrow. Tune in!

Tags:

Day 82

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Because the Common Core Grade 1 Math Standards address addition and subtraction exclusively, they will appear here later, in conjunction with the blocks that focus on the 4 processes. Earlier math blocks focus on meeting the numbers up close and personal through stories, movement, art, form drawing, and hands-on activities like making real numbers. The numbers should come together for calculation only after an in-depth introduction has established them as friendly and personable, so essential for circumventing math fears and phobias!

Yay! Back to math. That was quite a foray into CCSS Language Arts Standards. I will not be focusing on it to that extent with the other grades, but I wanted to point out that math does not exist in a vacuum. It works best when it’s cross-curricular in nature. Stories, art, and movement are such an essential part of a truly effective education, that needed space as well. I will touch on Language Arts Standards briefly in the other grades.

The second math block should focus on making real numbers. Why? Our base-ten, Arabic numeral system is simple to grasp; there are only 10 number forms to learn, 0-9. These numbers however, have little to no correlation to their visual appearance, as the Roman numerals do. Since they’re more abstract in that way, learning and writing them can be challenging. For this reason, sculpting or forming the numbers by hand can be very helpful, and there are many ways to do this.

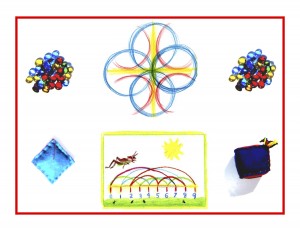

Consider using a variety of tactile methods, insuring that a hands-on or more body based knowledge will always underscore abstract learning. The possibilities are endless, and remember that large and colorful is always best. Here are a few suggestions:

1) Use several different play clay recipes to sculpt the numbers.

2) Cut a set of numbers 0-9 out of colorful poster board, and tape them onto a wall.

3) Feature a different number at breakfast or lunch each day by cutting waffles or sandwiches into number shapes.

4) Wear the numbers, stenciled onto T-shirts or hats.

5) Use a bread recipe to make number-shaped loaves, or to make number pretzels.

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. More real numbers tomorrow (a bit of a blend with Montessori), making sandpaper numbers. Tune in!

Tags:

Day 81

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post will address the “Reading: Literature” segment of the CCSS Language Arts Standards for Grade 1. There are nine standards, sub-divided into four groups. I will summarize the standards here in blue rather than listing each separately, and then relate ambient content to them, one group at a time.

These standards are a good match with the rich story and literature content of the Waldorf Grade 1 curriculum. However, where the standards say reading, I will substitute “listening and retelling” since first graders have not yet learned to read independently. The Common Core’s approach is “top-down,” meaning that standards designed to produce college and career ready adults are filtered down (and not watered down) from Grade 12 through Kindergarten. “Bottom up” is a more developmentally appropriate approach since it would begin with seed curriculum to produce a healthier (and superior) end result.

The CCSS Language Arts Standards for Reading: Literature, Grade 1:

1) Key Ideas and Details:

Ask and answer questions about details in a text.

Retell stories, including key details, and demonstrate understanding of their central message or lesson.

Describe characters, settings, and major events in a story, using key details.

The Grade 1 fairy tales are retold by the children the next day. The story is taken in whole and of a piece, so there really aren’t any questions to speak of. Rudolf Steiner said that attempting to analyze a fairy tale is like pulling apart a flower. That was directed at adults, so it carries even deeper meaning for children. The stories are recounted in great detail (it really is amazing how much they remember at this age), and are understood at a very deep level, plunging so deep into the child’s consciousness that it is not possible to expect the child to extract abstract meanings like singling out the central message or lesson. Characters and major events are described in exacting detail by the child, with an inherent understanding of their relative importance.

2) Craft and Structure:

Identify words and phrases in stories or poems that suggest feelings or appeal to the senses.

Explain major differences between books that tell stories and books that give information, drawing on a wide reading of a range of text types..

Identify who is telling the story at various points in a text.

The Grade 1 circle time is rich with classic poetry, tongue twisters, songs, and verses. The portions of these that suggest feelings or appeal to the senses are experienced as such by the children. And it is this very immersion in feelings and the senses that make the Grade 1 day so lively and engaging. But again, the children should not be expected to point out specific parts and identify or correlate them with anything else. The literature must stand on its own and exert its good influence without abstract analysis. I suppose if it’s presented concretely rather than abstractly, differences between text types could be pointed out. But this must remain casual and incidental rather than be direct and instructional. Narrative features are appreciated and understood on a deep level, but not taken apart and analyzed now.

3) Integration of Knowledge and Ideas:

Use illustrations and details in a story to describe its characters, setting, or events.

Compare and contrast the adventures and experiences of characters in stories.

Each Grade 1 story is illustrated with a drawing that relates in some way to a letter or number. It is drawn by the teacher and taught to the children, along with a caption that captures significant detail from the story. Compare and contrast is a more advanced essay writing tool that is best saved for later grades.

4) Range of Reading and Level of Text Complexity:

With prompting and support, read prose and poetry of appropriate complexity for Grade 1.

The children learn an impressive number of classic poems and verses over the course of the Grade 1 year. A great amount of excellent literature is covered because stories are heard, not read, and poems are learned by heart. Because the limitation of grade-level (simplified) texts is removed by lifting the requirement of the first graders actually having to read them, the innate intelligence of the child is met with reverence and respect, by including a good deal of quality, complex material.

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. We will be heading back to math tomorrow, though not the Common Core just yet. I will not be covering the College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards portion of the Language Arts Common Core since these standards are, in my opinion, way beyond what a first grader needs to know or is capable of learning.

Tags:

Day 80

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post will address the “Reading: Informational Text” segment of the CCSS Language Arts Standards for Grade 1. There are ten standards, sub-divided into four groups. The rich story and literature content of the Waldorf Grade 1 curriculum allows the 6-7 year old the freedom to develop capacities that are stunted and neglected with an emphasis on lessons and materials that are overly abstract and developmentally inappropriate. Sorry, I just cannot wrap my mind around a first grader perusing the New York Times or a pamphlet or brochure for that matter.

I will summarize the standards here in blue rather than listing each separately since they’re a poor match with what might be considered appropriate and effective for Grade 1. And I will not even attempt to relate them to any Grade 1 material because it’s just too much of a stretch. Instead, I will attach a link (I now know how!), a wonderfully informative youtube on the stages of child development and how to teach to them appropriately. The Common Core’s approach is “top-down,” meaning that standards designed to produce college and career ready adults are filtered down (not so much watered down) from Grade 12 through Kindergarten. “Bottom up” would be a more developmentally appropriate approach: beginning with seed curriculum to produce a healthier (and superior) end product.

The CCSS Language Arts Standards for Reading: Informational Text, Grade 1 are divided into four groups:

1) Key Ideas and Details:

Ask and answer questions about details in a text.

Identify the main topic and retell key details of a text.

Describe the connection between two individuals, events, ideas, or pieces of information in a text.

2) Craft and Structure:

Ask and answer questions to help determine or clarify the meaning of words and phrases in a text.

Know and use various text features (e.g., headings, tables of contents, glossaries, electronic menus, icons) to locate key facts or information in a text.

Distinguish between information provided by pictures of other illustrations and information provided by the words in a text.

3) Integration of Knowledge and Ideas:

Use the illustrations and details in a text to describe its key ideas.

Identify the reasons an author gives to support points in a text.

Identify basic similarities in and differences between two texts on the same topic (e.g., in illustrations, descriptions, or procedures.

4) Range of Reading and Level of Text Complexity:

With prompting and support, read informational texts appropriately complex for Grade 1.

This is a lot of age-inappropriate content, and the fact that the standards are tied to high-stakes testing (i.e., teachers whose students score poorly risk job loss, or students who score poorly risk being retained in a lower grade or being classified as special needs) makes it intolerably stressful for teachers, children, and parents alike. This is reflected in radically increased lesson prep time and translated into worksheets for both seat work at school and overly time consuming homework. And as such, it is an inefficient use of teacher/student abilities and resources.

Please watch Donita Brown in an excellent video, a comprehensive overview of just what is and isn’t appropriate for the lower grades. Note the short and long term effects of the extreme stress children are under with Common Core cramming and testing.

#mce_temp_url#

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. More CCSS ELA Standards tomorrow!

Tags:

Tags:

Day 78

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post will address the “Writing” segment of the CCSS Language Arts Standards for Grade 1. All seven of these standards reflect learning and material that will be present in later grades. The rich story and literature content of the curriculum allows the 6-7 year old the freedom to develop capacities that are stunted and neglected with an emphasis on lessons and materials that are overly abstract and developmentally inappropriate.

I will summarize the standards here in blue rather than listing each separately since they’re a poor match with what might be considered appropriate and effective for Grade 1. The Common Core’s approach is “top-down,” meaning that standards designed to produce college and career ready adults are filtered down (not so much watered down) from Grade 12 through Kindergarten. “Bottom up” would be a more developmentally appropriate approach: beginning with seed curriculum to produce a healthier (and superior) end product.

The CCSS Language Arts Standards for Writing, Grade 1 are divided into three groups:

1) Text Types and Purposes

Write opinion pieces about a topic of choice or a book, with reasons and closure.

Write informative/expository texts about a chosen topic, factual with closure.

Write narratives that include two or more events with time-sequencing and closure.

2) Production and Distribution of Writing

With adult guidance and support, focus on a topic, take questions/suggestions from peers, add details.

With adult guidance and support, collaborate with peers to use a variety of digital tools to produce/publish writing.

3) Research to Build and Present Knowledge

Share in research/writing projects like reviewing “how-to” books, then using them to write a list of instructions.

With adult guidance and support, gather information from experience or provided sources to answer a question.

This is confusing material for both teachers and students, reflected in radically increased lesson prep time and translated into worksheets for both seat work at school and overly time consuming homework. And as such, it is an inefficient use of teacher/student abilities and resources. First graders are not developmentally ready to take on these highly abstract tasks. Rather, exposure to good literature through storytelling or reflections on relationship to others and the world through nature stories can provide the necessary preparation for excellent writing skills later on.

If seeds such as these are planted in good, nurturing soil, watered and cared for, college and career ready adults will be the end result. But beyond college and career readiness, if the stages of development are properly heeded and the child is gradually gifted with the fruits of human heritage on this planet, s/he will carry a truly moral consciousness forward to address any and all of the future challenges presently developing on so many fronts.

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. More CCSS ELA Standards tomorrow!

Tags:

Day 77

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post will address the “Speaking and Listening” segment of the CCSS Language Arts Standards for Grade 1. All eight of these standards are covered by the stories that are told to and retold by the child(ren) and they will all be listed in blue, then related to the storytelling and retelling.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL 1.1

Participate in collaborative conversations with diverse partners about grade 1 topics and texts with peers and adults in small and larger groups.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL 1.1A

Follow agreed-upon rules for discussions (e.g., listening to each other with care, speaking one at a time about the topics and texts under discussion.)

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL 1.1B

Build on others’ talk in conversations by responding to the comments of others through multiple exchanges.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL 1.1C

Ask questions to clear up any confusion about the topics and texts under discussion.

Collaborative conversations occur quite naturally and regularly as the child(ren) retell the story the next day. Each and every detail is recounted almost verbatim as the entire story is carefully pieced together.

A) Amazingly, no rules are needed because the story is so compelling it carries the day by eclipsing any need or desire to digress! Turns are taken quite readily as the need to be true to the story wins out over attention-getting or stepping on each other’s toes.

B) Multiple exchanges happen as the story is pieced together. At this age it is unreasonable to expect a more mature mode of conversation, so instead the wonderfully complex exchanges and conversations found in any and all of the fairy tales provide a warm, nurturing cloak that protects the young child as s/he learns by example how to relate to others.

C) Not many questions are asked in the process of retelling because the story is accepted by the child(ren) as all of a piece. Appropriate to this age, the story acts as a security blanket, demanding little while providing a “whole cloth” picture of the world the child is growing into.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL 1.2

Ask and answer questions about key details in a text read aloud or information presented orally or through other media.

See (C) above.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL 1.3

Ask and answer questions about what a speaker says in order to gather additional information or clarify something that is not understood.

See (C) above.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL 1.4

Describe people, places, things, and events with relevant details, expressing ideas and feelings clearly.

All of the above are recounted in total recall and exact, relevant detail as the story is retold. The child is able to express (purely empathetically) the ideas and feelings of the characters in the fairy tale. This is all taken in on a very deep level, not yet made conscious or abstract because to do so would be beyond the intellectual and emotional capacity of the 6-7 year old. Extracting these feelings and ideas before the child has reached readiness is damaging and must be avoided.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL 1.5

Add drawings or other visual displays to descriptions when appropriate to clarify ideas, thoughts, and feelings.

After the story is retold, the child follows the teacher’s guidance to draw and caption an illustration of it. A number or letter, closely related to the story, is drawn on the facing page. Cloaking the letters and numbers in the beauty of the fairy tale protects the child’s not yet mature intellect by acting as a buffer, concretizing otherwise abstract concepts. (See this blog, Day 76 for Piaget’s recommendations re intellectual readiness.)

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL 1.6

Produce complete sentences when appropriate to task and situation.

the Waldorf first grader learns to read through writing, beginning with copying the stories’ captions in complete sentences. With Waldorf, learning to read is not rushed, often waiting until Grade 3. My daughter, a Waldorf student from Grades 1-8, did not read independently until then, when she jumped right into chapter books, with no need for primary readers.

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. More CCSS ELA Standards tomorrow!

Tags:

Day 76

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Uh oh, I know we’re all wanting to get back to the Common Core (are we?) but I’m taking another day here to post Jean Piaget’s stages of growth and development. Piaget (1896 – 1980) was a Swiss psychologist who was the first to systematically study cognitive development. Before his work, the common assumption in psychology was that children are merely less competent thinkers than adults. Piaget showed that children think in very different ways than adults, and that their cognitive development consistently follows a series of stages.

Piaget said, “The principle goal of education in the schools should be creating men and women who are capable of doing new things, not simply repeating what other generations have done.” And, “Only education is capable of saving our societies from possible collapse, whether violent or gradual.” Relevant words for today, and a possible wake-up call that we need to proceed thoughtfully and cautiously when instituting changes in educational policy. In light of this and in light of the controversy it’s raising, we may need to reevaluate the wisdom and effectiveness of the Common Core.

Good old Wikipedia supplied this summary of Piaget’s theory. It closely parallels Steiner and the Waldorf philosophy, in the recognition that the child is not ready to be formally taught until age 7, and that from ages 7 to 11 is not able to learn abstractly, but rather needs to be taught concretely. To this Steiner added the idea that the natural language of the child at this age is not only concrete but also rooted in the pictorial and artistic. Here are Piaget’s stages, and please do read them with the abstract nature of the Common Core Standards for Grades K-6 in mind.

Sensorimotor Stage: Ages 0 to 2

The sensorimotor stage is the first of the four stages in cognitive development which “extends from birth to the acquisition of language.” In this stage, infants progressively construct knowledge and understanding of the world by coordinating experiences with objects. Infants gain knowledge of the world from the physical actions they perform within it. They progress from reflexive, instinctual action at birth to the beginning of symbolic thought toward the end of the stage.

Pre-Operational Stage: Ages 2 to 7

Piaget’s second stage, the pre-operational stage, starts when the child begins to learn to speak at age two and lasts up until the age of seven. During the Pre-operational Stage of cognitive development, Piaget noted that children do not yet understand concrete logic and cannot mentally manipulate information. Children’s increase in playing and pretending takes place in this stage. The pre-operational stage is sparse and logically inadequate in regard to mental operations. The child is able to form stable concepts as well as magical beliefs. The child, however, is still not able to perform operations, which are tasks that the child can do mentally, rather than physically.

Symbolic function substage: Ages 2 to 4

At about two to four years of age, children cannot yet manipulate and transform information in a logical way. However, they now can think in images and symbols. Other examples of mental abilities are language and pretend play. Symbolic play is when children develop imaginary friends or role-play with friends. Children’s play becomes more social and they assign roles to each other. Some examples of symbolic play include playing house, or having a tea party.

Intuitive Thought Substage: Ages 4 to 7

At between about the ages of 4 and 7, children tend to become very curious and ask many questions, beginning the use of primitive reasoning. There is an emergence in the interest of reasoning and wanting to know why things are the way they are. Piaget called it the “intuitive substage” because children realize they have a vast amount of knowledge, but they are unaware of how they acquired it.

Concrete Operational Stage: Ages 7 to 11

The concrete operational stage is the third of four stages from Piaget’s theory of cognitive development. This stage, which follows the preoperational stage, occurs between the ages of seven and 11 years, and is characterized by the appropriate use of logic. During this stage, a child’s thought processes become more mature and “adult like”. They start solving problems in a more logical fashion. Abstract, hypothetical thinking has not yet developed, and children can only solve problems that apply to concrete events or objects. Piaget determined that children are able to incorporate inductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning involves drawing inferences from observations in order to make a generalization. In contrast, children struggle with deductive reasoning, which involves using a generalized principle in order to try to predict the outcome of an event. Children in this stage commonly experience difficulties with figuring out logic in their heads. For example, a child will understand that “A is more than B” and “B is more than C”. However, when asked “is A more than C?”, the child might not be able to logically figure the question out in their heads.

Formal Operational Stage: Ages 11 to 15-20

The final stage is known as the formal operational stage (adolescence and into adulthood, roughly ages 11 to approximately 15-20): Intelligence is demonstrated through the logical use of symbols related to abstract concepts. At this point, the person is capable of hypothetical and deductive reasoning. During this time, people develop the ability to think about abstract concepts.

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. We will go back to the CCSS ELA Standards tomorrow!

Tags: