Day 75

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Oh no, yesterday’s post was so much fun, I find myself having trouble getting back to the Common Core. I’m hearing that it can be crafted into dynamic and interesting lessons, and I’m trying! But it does take a lot of effort to do that, and I can only imagine that adding the “testing” factor ratchets it all up to high stress levels, especially with the high-stakes nature of the tests for all concerned: children, teachers, and schools.

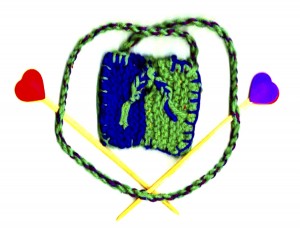

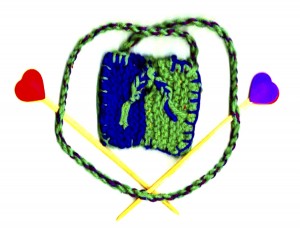

Anyway, I’m taking another day off to breathe before diving into deep Common Core waters again. Knitting is learned by all Waldorf first graders. If they had experience with finger knitting, helping with simple sewing, and other engaging crafts in the Kindergarten, they will be somewhat more prepared to take on knitting. They can start simply, with just a six inch square. After making their own knitting needles with sharpened dowels, a bead at the end and beeswax polish, they’re ready to learn. I will devote a post to knitting, including a verse and detailed instructions, at the end of the Grade 1 section.

In the meantime, here’s a wonderful youtube by Renate Hiller, Master Waldorf Handwork teacher. (Sorry if this is not a live link, one of these days I will learn how to insert media in these posts!)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bfoByYLSBY8

And just for fun, here’s a project that you can knit with your child(ren)’s help, as an inspiring motivator, before they themselves learn how to knit (see the image at the bottom of this post). Knowledge, remember, ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. We will go back to the CCSS ELA Standards tomorrow!

First, make a pair of knitting needles using chopsticks or dowels. You can buy chopsticks in packs at a Chinese grocery store, or recycle the ones you used at your last visit to a Chinese restaurant. Here’s how to make a pair:

1) Sharpen the chopsticks or dowels in a pencil sharpener.

2) Sand them with fine sandpaper to blunt the points a bit.

3) Apply an emollient (like shea butter or beeswax) and rub it in well.

4) Attach beads, clay, or foam “stickies” as stoppers (use a few drops of glue as well to secure them).

5) Knit!

Make the coin pouch by knitting two rectangles as shown, in contrasting colors. Join the pieces in the middle with a running “V” stitch, leaving a small opening toward the top in front.

Fold a braided tie (made with the same yarns) in half, attach it with a few stitches to the top back, pull one end through the front opening, and tie. The handle is a piece of mini “rope” that’s easy to make:

1) Cut 3 pieces of yarn 3 times longer than the length you need the finished rope to be.

2) With a partner, hold both ends and keep the yarn very taut while twisting in opposite directions. If alone, tape one end to a surface and twist in one direction.

3) When it’s twisted so tightly that it begins curling up on itself, carefully fold the twisted strand in half and let go, while smoothing the two strands together. Tie the open ends. Rope!

Finish the edges with a blanket stitch using contrasting yarn on each side, leaving a couple inches open on top. Kitting is a wonderful right-left brain integration activity and helps with many skills that are useful for math as well. Crafts and math are an excellent match, so do generously add crafts and hands-on activities to your math lessons!

Tags:

Day 74

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today was challenging, wrestling with materials to create more Math By Hand kits and packages. It’s all good, but some days are less good than others. A little break from the Common Core would be nice too, hence this shorty blog . . .

Morning circle is a good time to recite, hop, skip, sing, and dance. Wonderful activity for waking up and getting ready for an exciting day of learning. Grade 1 rhymes tend to be basic, traditional, and strongly rhythmic. They are fairly easy to learn and are excellent lead-ins to rhythmic counting, skip counting, and first times tables. Pair finger-plays and movement with these familiar rhymes as well. Here are some excerpts from the Math By Hand Rhythms ‘n’ Rhymes booklet.

Sally go round the sun,

Sally go round the moon,

Sally go round the chimney pots,

On a Saturday afternoon.

Wee Willie Winkie runs through the town,

Upstairs and downstairs, in his nightgown,

Knocking on the window,

Crying through the lock

“Are the children all in bed?

It’s past eight o’clock.”

Head, shoulders, knees and toes,

Knees and toes,

This is the way my body goes.

Ears, eyes, nose and mouth,

Nose and mouth,

This is the way my face goes.

Whether the weather be fine

Or whether the weather be not,

Whether the weather be cold

Or whether the weather be hot,

We’ll weather the weather

Whatever the weather,

Whether we like it or not.

The elephant is like a wall,

He is so very broad and tall.

Upon his back we have a ride,

And swing and sway from side to side.

Tongue twisters are not only great fun, they’re also helpful for honing speaking and listening skills. Include them as a regular morning circle treat. Here are several from the Math By Hand Tongue Twister booklet.

Lovely lemon liniment.

Fat frogs flying past fast.

Tim, the thin twin tinsmith.

Flee from fog to fight flu fast.

6 thistle sticks, 6 thick thistles stick.

Any noise annoys an oyster but a noisy noise annoys an oyster most.

Take a cue from your littles and always have fun with it all. As W. B. Yeats so wisely said, “Education is not the filling of a pail but the lighting of a fire.” Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. Back to the CCSS ELA Standards tomorrow!

Tags:

Day 73

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Because the Common Core Grade 1 Math Standards address addition and subtraction exclusively, they will appear here later, in conjunction with the blocks that focus on the 4 processes. Earlier math blocks focus on meeting the numbers up close and personal through stories, movement, art, form drawing, and hands-on activities like making real numbers. The numbers should come together for calculation only after an in-depth introduction has established them as friendly and personable, so essential for circumventing math fears and phobias!

The original goal of this blog was to ambiently interpret the math standards, but I must also expand it to include language arts standards. Waldorf and Waldorf-inspired curriculums are deeply cross-curricular. Today, the next eight standards (which will appear in blue) will be reviewed, followed by their ambient counterparts (references may be made throughout to “The Prince in the Black Scarf.” Please return to it and review as needed. (Note: Knowledge of Language L1.3 begins in Grade 2.)

Vocabulary Acquisition and Use:

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.4

Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiple meaning words and phrases based on Grade 1 reading and content, choosing flexibly from an array of strategies.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.4A

Use sentence level context as a clue to the meaning of a word or a phrase.

The frequency and rich content of storytelling in Grade 1 (fairy tales of the length and complexity of “The Prince in the Black Scarf” are told three to four days a week in both the language arts and math blocks) insures that complex and compound sentences are spoken and heard consistently. This lays a solid foundation for a more direct experience with reading and writing later on. Nothing improves vocabulary like reading or hearing great literature. New words are learned within the rich tapestry of the story, very much in context.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.4B

Use frequently occurring affixes as a clue to the meaning of a word.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.4C

Identify frequently occurring root words (e.g., look) and their inflectional forms (e.g., looks, looked, looking.

Exploration of the root, prefix and suffix word structure can happen very colorfully and playfully in second or third grade. But here and now, in Grade 1, it’s a bit too analytical. A foundation could be built for later by color coding some words as they are written in the captions or excerpts from the stories. Writing in Grade 1 could be done with crayons or chunky colored pencils rather than lead pencils, and then some select words (not too many) could be color coded by their roots and affixes. No need to teach directly at this point.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.5

With guidance and support from adults, demonstrate understanding of word relationships and nuances in word meanings.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.5A

Sort words into categories (e.g., colors, clothing) to gain a sense of the concepts the categories represent.

Foreign languages are taught from the Waldorf Grade 1 on through the grades. And they are taught in just this playful way: the teacher might bring a suitcase full of clothes, pull them out one by one, saying each one’s name. Or for food names, s/he may unpack a picnic basket. This could be done with English as well, since in some sense it’s still a foreign language for the child(ren).

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.5B

Define words by category and by one or more key attributes (e.g., a duck is a bird that swims, a tiger is a large cat with stripes).

Nature and animal poetry comes to mind here. A good deal of poetry is learned in the morning circle time. Recitation is an excellent way to access many skills like speaking, memorization, rhythmic sense, to name just a few. And the sense of accomplishment and joy gained in having learned something by heart is immense. Find this sort of word play and categorization there.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.5C

Identify real-life connections between words and their use (e.g., note places at home that are cozy).

This can be accomplished through simple, everyday conversations between teacher or parent and child. If a child is spoken to with a conscious awareness of these connections on the adult’s part, s/he will absorb them. And “absorb” is key here, as the most efficient, effective, and painless method of learning such things.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.5D

Distinguish shades of meaning among verbs differing in manner (e.g., look, peek, glance, stare, glare, scowl) and adjectives differing in intensity (e.g., large, gigantic) by defining or choosing them or by acting out the meanings.

Great fun can be had here by acting out the meanings of both of the above, again through poetry or songs (with lots of movement, ham it up here!) in the morning circle time. Parent or teacher made ones are fine if none can be found.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.6

Use words and phrases acquired through conversations, reading and being read to, and responding to texts, including using frequently occurring conjunctions to signal simple relationships (e.g., because).

Any literature or any good conversation is replete with compound, not simple sentences. Everyday conversations with your child(ren) that honor their native intelligence will have frequently occurring compound sentences, complete with a wealth of conjunctions. You can also be sure to include them and all of this standard’s requirements in the captions that accompany the story illustrations. Responses to text occur continually throughout Grade 1 in the story retell.

I must say that finding my way through these standards is difficult. It’s difficult to find the joy so necessary for effective, successful teaching within their confines. I flashed back to a teacher’s blog I read recently, stating that he continually sees other teachers crying in their cars in the school parking lot in the morning, just not able to find the strength to go into the building. I experienced this sadness myself tonight, trying to bring these standards to life.

More than ever, remember that knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. More CCSS ELA tomorrow!

Tags:

Day 72

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Because the Common Core Grade 1 Math Standards address addition and subtraction exclusively, they will appear here later, in conjunction with the blocks that focus on the 4 processes. Earlier math blocks focus on meeting the numbers up close and personal through stories, movement, art, form drawing, and hands-on activities like making real numbers. The numbers should come together for calculation only after an in-depth introduction has established them as friendly and personable, so essential for circumventing math fears and phobias!

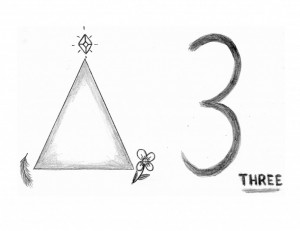

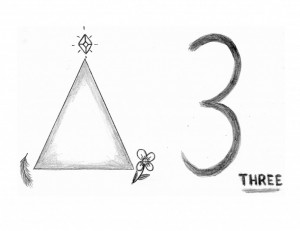

Before beginning the Grade 1 Common Core Language Arts Standards, just a few words about the story “The Prince in the Black Scarf,” and how Math By Hand relates it to the number 3. Both a related story and a geometric form are chosen for each number. I chose this story for its focus on the family of three: the king, the queen, and the prince. The dynamic of this family relationship is a familiar one, easily accessed by the child(ren) as a reference. This pairing of number and concept is elaborated upon after the story is retold by the child(ren), and helps immeasurably to act as a placeholder for the number 3, making it concrete rather than abstract and thus more accessible and friendly.

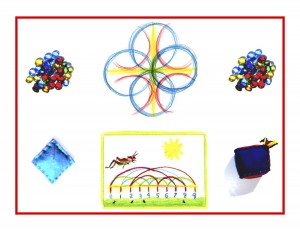

I chose the triangle for the number 3, as I chose the square for the number 4, the hexagon for the number 6, etc. Again, this pairing helps for the same reasons cited above, but also acts as a foundation for later concepts in geometry, bringing both the simple numbers and geometry alive by “befriending” them. When art and literature are paired with learning in all subjects, it not only anchors the mundane, abstract concepts in beauty (the native language of the young child), it also helps build a foundation for a life long love of and affinity for learning and the arts. The drawing below interweaves the triangle (geometry) with elements of the story (see the objects at each point of the triangle). Include a more direct illustration for each story as well. For this one, a simple drawing of the king, queen, and prince, captioned in uppercase letters, “THREE IS A FAMILY” would work.

If you read through the whole story the day before yesterday, you know how intricate and complex it is. All elements of literature are embedded in this and other ancient fairy tales. Amazingly, when the story is retold the next day by the child(ten), every nuance is captured, almost word-for-word. At age 6 or 7, the powers of memory are still strong, unlike ours as adults. Conversely, please note that every less than optimal exposure (such as most media) is also deeply and indeed indelibly embedded in the child’s developing brain and consciousness. As characterized by Steiner the fairy tales are “deeply moral.” So that the desirable qualities (justice, fairness, compassion . . .) we might wish to instill in our children are there. They are not directly preached, but subtly conveyed (and this is a crucial difference).

The Common Core Standards if applied as written are most direct, and as such do not (unless very broadly and ambiently interpreted), speak the language of the young child. The original goal of this blog was to ambiently interpret the math standards, but I must expand this to include language arts standards as well, because Waldorf and Waldorf-inspired curriculums are deeply cross-curricular. Today, the first 15 standards (which will appear in blue) will be reviewed, followed by their ambient counterparts (references may be made throughout to “The Prince in the Black Scarf.” Please return to it and review as needed.

Conventions of Standard English:

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.1

Demonstrate conventions of standard english grammar and usage when writing and speaking.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.1A

Print all upper and lower case letters.

In Grade 1, captions taken from the story are printed/copied from the teacher’s example by rote, because the letters of the alphabet are being introduced singly and in depth, over the whole year. Slowly and pictorially is key for best learning and absorption because of the abstract nature of reading and writing.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.1B

Use common, proper, and possessive nouns.

In reading and reviewing the story, you will find all of the above in abundance. Now is not the time to pull it apart, but rather the story is left intact with all of its elements, to take root in a more unconscious realm, to be taken up later as in second or third grade formal grammar structure is playfully and artfully taught.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.1C

Use singular and plural nouns with matching verbs in basic sentences (e.g., He hops; We hop).

Basic sentences should be avoided. We often disrespect the wisdom of young children by teaching down to them. The traditional young reader books like the Dick and Jane series or “See Spot Run” are demeaning. If allowed to learn the mechanics slowly, children never need to read boring or condescending content.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.1D

Use personal, possessive, and indefinite pronouns (e.g, I, me, my; they, them, there, anyone, everything).

Again let this occur naturally, in the context of excellently crafted literature. Do not drill these things directly, since “drill and kill” is real. It kills the spirited, creative spirit of curiosity and inquiry nascent in the young child.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.1E

Use verbs to convey as sense of past, present, and future (e.g., Yesterday I walked home; Today I walk home; Tomorrow I will walk home).

This can be accomplished through simple, everyday conversations between teacher or parent and child. If a child is spoken to with correct grammatical structure, s/he will absorb it. And “absorb” is key here, as the most efficient, effective, and painless method of teaching such things. We are losing the glue of human interaction as conversation becomes a lost art, as we devote more and more hours to the digital world.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.1F

Use frequently occurring adjectives.

Reread the little excerpt from “Sylvester and the Magic Pebble.” Steig is a master of the prolific adjective. His books and others like them have complex plots, examples of noble traits, and excellently rich vocabulary, to fill the bill nicely.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.1G

Use frequently occurring conjunctions (e.g., and, but, or, so, because).

Any literature or any good conversation is replete with compound, not simple sentences. Everyday conversations with your child(ren) that honor their native intelligence will have frequently occurring compound sentences, complete with a wealth of conjunctions. You can also be sure to include them and all of these standard requirements in the captions that accompany the story illustrations.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.1H

Use determiners (e.g., articles,demonstratives).

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.1I

Use frequently occurring prepositions (e.g., during, beyond, and toward).

These are both easily conveyed with frequent, lively conversation, again most effectively through absorption and osmosis, the way language is learned by the very young.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.1J

Produce and expand complete simple and compound, declarative, interrogative, imperative, and exclamatory sentences in response to prompts.

Much of this is conveyed by inflection when telling stories or when speaking in everyday conversation. The correct punctuation for each type ( . ? ! ) should used in the text written by the teacher and copied by the student(s). Prompts and drills are counterproductive if excessively used.

Conventions of Standard English:

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.2

Demonstrate conventions of standard english capitalization, punctuation, and spelling when writing and speaking.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.2A

Capitalize dates and names of people

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.2B

Use end punctuation for sentences.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.2C

Use commas in dates and to separate single words in a series.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.2D

Use conventional spelling for words with common spelling patterns and for frequently occurring irregular words.

All of these are taught through imitation at this point, by copying the correctly worded and punctuated text the teacher provides, enabling correct punctuation and spelling to become second nature through exposure and absorption.

CCSS ELA-LITERACY L1.2E

Spell untaught words phonetically, drawing on phonemic awareness and spelling conventions.

“Invented spelling” may not be necessary with enough exposure to correct spelling in copied text and taught word building later on. First, the words are copied correctly, then word building can be taught directly but playfully and artfully in a later grade (through root words and the structure of words).

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. More CCSS LA tomorrow!

Tags:

Day 71

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Because the Common Core Grade 1 Math Standards address addition and subtraction exclusively, they will appear here later, in conjunction with the blocks that focus on the 4 processes. Earlier math blocks focus on meeting the numbers up close and personal through stories, movement, art, form drawing, and hands-on activities like making real numbers. The numbers should come together for calculation only after an in-depth introduction has established them as friendly and personable, so essential for circumventing math fears and phobias!

It seems I’ve been sidetracked. Just wanted to insert a post or two re the number stories and the other language-rich aspects of an integrated math curriculum and how it all relates to the Common Core Language Arts Standards. After reviewing said standards, I felt compelled to explore how the Waldorf method does so much more than the Common Core requires. The 90-some Grade 1 CCSS Language Arts Standards will be reviewed and juxtaposed alongside their ambient counterparts, over the next eight or so blog posts.

Meanwhile, please consider the intricate complexity of yesterday’s story, “The Prince in the Black Scarf.” This is the level of literature that permeates the Grade 1 curriculum, forming the backbone and scaffolding of a well-rounded, complete year of learning. I hope to rise to the challenge of favorably comparing the subtleties of the Waldorf approach to the direct, abstractly analytical Common Core. Yesterday’s fairy tale will carry the impetus for this comparison. Wish me luck!

I once attended a teacher’s in-service for promoting literacy and literature appreciation where a speaker extolled the books of William Steig, a famous cartoonist who began writing children’s books at 61. The speaker focused on the complexity of Steig’s writing, how it stretched the literary capacity of the children who read it (or had it read to them). His books were mine and my daughter’s favorites. We read them all! As previously mentioned, she did not learn to read independently until the beginning of Grade 4, and is now a brilliant PhD candidate at Cal Berkeley. So please take heed: slow learning really is best.

Here is an excerpt from Steig’s “Sylvester and the Magic Pebble.” Note the complexity of the language and structure, and look down below for some lovely images of Sylvester and his family. Remember that knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal.

Sylvester Duncan lived with his mother and father at Acorn Road in Oatsdale. One of his hobbies was collecting pebbles of unusual shape and color. On a rainy Saturday during vacation he found a quite extraordinary one. It was flaming red, shiny, and perfectly round, like a marble. As he was studying this remarkable pebble, he began to shiver, probably from excitement, and the rain felt cold on his back. “I wish it would stop raining,” he said. To his great surprise the rain stopped. It didn’t stop gradually as rains usually do. It CEASED. The drops vanished on the way down, the clouds disappeared, everything was dry, and the sun was shining as if rain had never existed.

Tags:

Day 70

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Because the Common Core Grade 1 Math Standards address addition and subtraction exclusively, they will appear here later, in conjunction with the blocks that focus on the 4 processes. Earlier math blocks focus on meeting the numbers up close and personal through stories, movement, art, form drawing, and hands-on activities like making real numbers. The numbers should come together for calculation only after an in-depth introduction has established them as friendly and personable, so essential for circumventing math fears and phobias!

Starting tomorrow, before leaving the realm of meeting the numbers 1-12 through stories, a detour into the Common Core Grade 1 Language Arts Standards will begin. As analytical and direct as these standards are, my posts over the next several days will attempt to show how the Waldorf method’s whole-to-parts approach can accomplish more in the long run, while also keeping the desire to learn with joy, excitement and enthusiasm alive through story, art, and movement. To whet your appetite, here is the story Math By Hand pairs with the number 3, a fairy tale from France called “The Prince in the Black Scarf.”

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal.

Once upon a time there lived a very wealthy King of France. He was very wise and was loved by all his people. He had a beautiful Queen who gave him a son. The Prince grew into a handsome youth. He soon reached his seventeenth year. But then the Prince fell into bad company, drinking and gambling. The people of the Kingdom feared he would never make a good King when his father died. “Your son must be taught a lesson,” said the elders of the city to the King. The first time they complained, the King ordered the Prince to be given a hundred lashes, but he soon fell back into his old ways.. The second time they complained, he was whipped and sent to prison for one year. Again he returned to his bad friends. The third time the elders complained the King promised that his son would be executed. The elders tried to calm him, but the King was deter-mined. The Queen ran to find the Prince first. “Here is a bag of gold, your sword, and your horse. Go out into the world and find your true path. I do not want to see you again until you do.” The following morning the Queen told the King what she had done. The King was not angry but he said that if his son returned, he would send him to the gallows as he had promised. Meanwhile the Prince had ridden far across the Kingdom. He stopped to spend the night in a clearing in a forest. As he sat, he saw a hawk swoop down and catch a mouse. Then a vixen dashed out of the bushes and caught the hawk. Suddenly an arrow flew through the air, killing the vixen. As the huntsman rode up and leaned out of the saddle to pick up the fox, the string on his bow snapped. It flicked against his horse and made him bolt. The hunter was unseated but his foot was caught in the stirrup dragging him along. This all happened so quickly, the Prince did not have time to move. He thought carefully about what he had seen. He realized that one bad deed could only lead to another and that his father had been right to punish him. The Prince decided to change his ways. The following morning he sold his horse and gave all his money to the poor. He kept his sword and he put a tattered cloak over his fine clothes and put a black scarf over his head with holes for his eyes, nose, and mouth. After walking for seven weeks, the Prince found himself by a hut in the middle of a forest. A hermit lived in the hut. “Welcome, Prince of France,” he said to the Prince. “How do you know who I am?” asked the surprised Prince. “I know who you are and why you are here,” said the hermit. “Now leave me your sword, your fine clothes, and your scarf. Put on these old clothes, go to the end of this path and find work with the farmer there.” After seven days’ walk the Prince came to a farm. The farmer there took him on as a swineherd. He took the pigs every day to a field by the sea. One day, while he was there with the pigs, he heard a scream come from the edge of the forest, and he saw an old woman. Her goat was being dragged away by a wolf. The good Prince clubbed the wolf with his crook so that it dropped the goat and ran. “Thank you, Prince,” said the old woman. “When you need help, come to this hollow tree, knock three times and I shall come to your aid.” Then, she and the goat disap-peared in a mist. The Prince returned to the farm that evening to find the farmer with a troubled look on his face. The Prince asked him what was wrong. “A giant is roaming the French countryside. Wherever he goes the countryside dries up. He is turning France into a wasteland.” “Has no one tried to kill him?” asked the Prince. “The have tried, but they have all failed. The giant cannot be destroyed.” The next day, as the Prince was driving the pigs to pasture he stopped by the hollow tree and knocked three times. At his third knock, a beautiful girl appeared. “Good day, Prince,” she said. “I know why you are here. Listen carefully. If you wish to slay the giant you must strike his diamond eye with your sword. Fetch your clothes, sword, and black scarf and follow the midday sun for seven days until you reach a dry plain. Hide inside the ruined castle there and wait. The giant will come as night falls. He will stretch out across the plain and go to sleep. On the stroke of midnight you must strike him with your sword.” With that the girl disappeared. The swineherd said goodbye to the farmer and returned to the hermit’s hut where he collected his belongings. After seven days’ walk, he reached the ruined castle on the plain. As night fell, the giant returned to the plain and lay down to sleep. At the stroke of midnight, the Prince came out of his hiding place and struck the giant in his diamond eye. The giant sighed and then disappeared. All that was left was the diamond eye. The Prince picked up the diamond and, still wearing his black scarf, he took it to the French court. He saw the Queen looking out of the window but she did not see him. “I bring you the diamond eye of the giant, sire,” said the Prince to the King, “as proof of the giant’s death.” “Thank you, man in the black scarf,” said the King. I will reward you with one hun-dred thousand gold coins for slaying the giant.” I do not fight for reward, but for honor,” said the Prince in the black scarf. “If you do not need the money, then give it to the poor.” “I see you are noble as well as brave,” said the King. “Show me your face.” I cannot, sire, replied the Prince. “My father wishes never to see my face again, so I cannot uncover it, even for you.” “Your father should be proud of you,” said the King. My own son is a failure.” “I know him well, sire,” said the Prince. “He has changed a great deal.” “I find that hard to believe,” said the King. “If I lay eyes on him I shall send him straight to the gallows.” The Prince left the King, but he waved once to the Queen. He returned to the hermit at the edge of the forest. “Welcome, Prince,” said the hermit. “How did you get on?” “I killed the giant, and took his diamond eye to my father, the King. But he will not have me back,” said the Prince. “That is because you have not been fully tested,” said the hermit. “Return to your work at the farm.” The Prince left his belongings with the hermit and returned to the farmer and again became a swineherd. He drove the pigs to the meadow by the sea every day. Several weeks passed, and one day as he was sitting watching the pigs, a golden bird settled in the branch above his head. “Good day, Prince,” said the golden bird. “I am the golden bird who will live forever. Every hun-dred years I must have a drink of human blood or I shall die. Good Prince, will you help me, as today it is one hundred years since I last drank?” “Of course, I will help you,” said the Prince. “Fly down and drink.” So saying, the Prince cut his arm and the bird flew down and drank. “Good Prince, when you need my help, come to these woods and clap three times,” said the bird, when it had finished drinking. It then flew away. At the end of the day the Prince returned to the farm. There he found the farmer looking very sad. He asked him what was wrong. “A terrible dragon has come to the land. It is catching people and animals and eating them. Nothing can stop it.” “Hasn’t the King sent soldiers against it?” asked the Prince. “Indeed, but it is too big and strong. It has eaten many of them.” The next morning the Prince drove the pigs to the meadow, but he stopped by the woods and clapped his hands three times. “I know why you are here, Prince,” said the Golden Bird as it appeared on the branch. “Take this feather and put it in your mouth and you will change into a bird. Spit it out and you will change back. The dragon you seek can only be killed by stabbing it through the heart. Follow the midnight moon for seven nights until you reach some mountains. The dragon’s cave is there. You must fly into his open mouth and strike from the inside. Now, goodbye.” The Prince once again said goodbye to the farmer and returned to the hermit where he put on his fine clothes, his sword, and his black scarf. After seven nights of following the midnight moon, he reached the mountains. As night fell, the dragon with a golden crown on its head returned to its cave. It settled itself down to sleep. As its mouth opened the Prince changed into a bird and flew in. He flew down toward the dragon’s heart. There he spat out the feather and the Prince then stabbed the dragon’s heart with his sword. The dragon sighed and disappeared and all that remained was the gold crown. The Prince picked up the golden crown and took it at once to the French court. As he walked in, the Prince saw the Queen by the window. She turned and looked at him. “I have killed the dragon,” said the Prince as he gave his father the dragon’s crown. “Once again, you have done my Kingdom a great service,” said the King. I shall give you two hundred thousand gold coins as a reward.” If you do not need the money, give it to the poor,” said the Prince. I seek honor rather than reward.” “You are still a noble man,” said the King. “Let me see your face.” “Ah, no, your majesty,” said the Prince. “As I said before, I cannot show my face.” “Your father should be proud to have you for a son,” said the King. “My own son is a failure.” “I know him and he has changed,” said the Prince. “Can I not tell him that you would like to see him again?” “No,” cried the King. “If I see him he goes to the gallows.” The Prince turned and left, but he waved to the Queen. He returned to the hermit. “How did you fare?” “I killed the dragon and took its crown to my father, but he still will not have me back.” “That is because you have not been fully tested,” said the hermit. “Return to your work at the farm.” The Prince returned to the farm and again became the farmer’s swineherd. He drove the pigs to the pasture by the sea every day. One day he was sitting watching over the pigs, when a huge bird swooped down and came up with a large golden fish in its claws. The fish struggled to get free but the bird held on tight. So the swineherd leapt up and hit the bird with his crook so that it released the fish. The fish swam up to the Prince. “Thank you, Prince. When you need my help, you must throw three handfuls of sand into the sea, and I shall come.” Then the fish disappeared. The Prince returned to the farm in the evening with the pigs. When he entered the farmhouse, the farmer was looking very miserable indeed. “What’s wrong?” asked the Prince. “A terrible plague is sweeping across the country. The people are dying everywhere. They say that the King and Queen are ill with it.” “Is there no doctor who can help?” asked the Prince. Doc-tors have tried to find a cure, but even they are dying of it,” said the farmer. The next day the Prince said goodbye to the farmer. “I must go,” he said. He then went down to the sea and threw three hand-fuls of sand into the sea. As he threw the last handful the golden fish appeared. I know why you are here, Prince, and I will help you,” said the fish. “You must fetch the Golden Flower with the scent of balsam and plant it in the courtyard of the palace of the French King to rid the country of the plague. But the flower grows on an island in the middle of very rough seas. I will take you to it.” So saying, the fish took the Prince on his back and swam away from the shore across the sea. The seas were rough and stormy, but they finally reached the tiny island. “Go and collect the flower and I shall take you back to shore,” said the golden fish. The Prince leapt off and found the flower with the scent of balsam. He returned with it to the fish. The golden fish swam safely back through the mountainous waves and left the Prince on the beach near the hermit’s hut. Then the golden fish disappeared. The hermit came out of the hut with the Prince’s clothes, his sword, and the black scarf. “You will have to hurry. I have already saddled your horse,” said the hermit. The Prince put on his clothes and the black scarf and mounted the horse. He said farewell and galloped off to the French court. He was standing in the courtyard of the palace in no time. He dug a hole and planted the Golden Flower. Immediately the scent of balsam was everywhere. All the town and the Kingdom came to life again and the plague left the country. The Prince entered the palace. There he saw the Queen by the window. She saw the man in the black scarf and she jumped up. “Welcome, my son, I knew it was you.” She embraced her son fondly. Then the Queen and Prince hurried to the King’s room, where he lay in bed gravely ill. “Welcome, man in the black scarf,” said the King. “What brings you here?” “I have brought the Golden Flower with the scent of balsam to cure the kingdom of the plague.” “Thank you for this great service. I give to you my crown and my Kingdom, for I am old and my son is a failure who will never be King.” “I know him well and you do him an injustice,” said the Prince. “He is no more a failure than I am. He would dearly like to come back to you if you could forgive him.” “If he could be as good a son as you are, then I would forgive him,” said the King. “Then forgive him now,” cried the Prince as he pulled off the black scarf. Then the King recognized his son. He was overjoyed to see him. The old King ruled on and when he died the good Prince took over the reign of the Kingdom. Never was there so just or wise a King of France.

Tags:

Day 69

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Because the Common Core Grade 1 Math Standards address addition and subtraction exclusively, they will appear here later, in conjunction with the blocks that focus on the 4 processes. Earlier math blocks focus on meeting the numbers up close and personal through stories, movement, art, form drawing, and hands-on activities like making real numbers. The numbers should come together for calculation only after an in-depth introduction has established them as friendly and personable, so essential for circumventing math fears and phobias!

Here are excerpts from the Math By Hand Grade 1 Daily Lesson Plans book: Morning Circles. There are six in all, two for each of the three Grade 1 Math Blocks. The same content is usually kept for 2-3 weeks until the verses are learned and the skill sets mastered. There are two booklets included with the Math By Hand Grade 1 Complete Package. One features classic rhymes and verses and the other tongue twisters. You can find many examples of both online or at the library.

Counting by ones starts small and reaches 100 by the end of Grade 1, the 2, 5, and 10 times tables are rhythmically practiced until they are learned, and simple, single digit calculation in all 4 processes is practiced with a beanbag toss. Recitation is valuable for so many reasons, but the rhythmic element is directly applicable to math. All in all, the lively circle is the optimal way to start the day! So do enjoy singing, dancing, reciting, and learning math skills with your littles . . .

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. Tune in tomorrow for a review of stories and rhymes.

Choose from verses #1-8 in the Rhythms and Rhymes book and teach/learn them by heart.

Use finger plays with some verses. Here are suggestions for verses #1 and #6:

Blow wind blow cupped hands/pursed lips/blow

And go mill go both fists rotate/vertical circle

That the miller may grind his corn right fist rotates/horizontal circle

That the baker may take it both hands extended together/palm up

And into bread make it both hands palm down/form the loaf

And bring us a loaf in the morn. right hand extended/palm up/left hand under right forearm/palm down

Dr. Foster went to Gloucester right hand over eyes/palm down/looking ahead

In a shower of rain both hands extended up/palms in/brought down with fluttery fingers

He stepped in a puddle right foot lifted high/tip-toed down

Right up to his middle both hands palm down/at mid-torso

And never went there again. right hand index finger up/wags back and forth

Use one or several beanbags to accentuate the verses’ rhythm by tossing it back and forth in time, by passing it around the circle, or by switching hands, in front and back.

Use the beanbags for tossing and catching while counting by 1’s and 2’s.

Count by 1’s up to 50 and by 5’s up to 60, while walking in a circle. Begin with the tiptoe/whisper – marching/speaking pattern (1-2-3-4-5 6-7-8-9-10), later dropping the in-between numbers. Use the beanbags to accentuate the verses’ rhythms and to toss and catch while counting as well.

Practice single-digit, simple 4 Processes equations while throwing and catching the beanbag(s). Vary the patterns (underhand throw and catch / catch, switch hands behind the back, throw / throw beanbag up in the air and catch while saying 2’s / 5’s).

Choose a number of Tongue Twisters and say them, the more the merrier!

Accompany any of the verses with this clapping pattern, in partners:

Clap own hands / Clap partner’s hands / Slap knees / Clap own hands behind own back

Speak or sing memorized verses tapping rhythm sticks, waving a small flag, or playing a tambourine while walking, skipping, or hopping (on one or two feet) in a circle.

Tags:

Day 68

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Because the Common Core Grade 1 Math Standards address addition and subtraction exclusively, they will appear here later, in conjunction with the blocks that focus on the 4 processes. Earlier math blocks focus on meeting the numbers up close and personal through stories, movement, art, form drawing, and hands-on activities like making real numbers. The numbers should come together for calculation only after an in-depth introduction has established them as friendly and personable, so essential for circumventing math fears and phobias!

In reviewing the structure of the Grade 1 Daily Lesson Plans book, I’m remembering that the 20 days of the second math block is divided into 10 days of real numbers play and exploration and 10 days of introducing the 4 processes, using costumes, stories, and plays. Then the third math block is devoted to lots of 4 processes practice. I’d like to take a couple days to share the morning verse and one of the Math By Hand morning circles before moving on to exploring the real numbers. A verse is said first thing every morning in the Waldorf lower grades, and this is my version, followed by the verse that’s used in most Waldorf schools.

The Sun’s bright and golden eye

Brings light to me each day,

As Night’s black velvet curtain

Draws back and folds away.

I wake from sleep each morning

With a will to work and play,

As my head and heart and hands

Know all the world’s my home.

I gather all my might

To love to work and learn,

With strength, in shining light:

My loving thanks I will return.

Marin Lipowitz

The Sun with loving light

Makes bright for me each day,

The soul with spirit power

Gives strength unto my limbs,

In sunlight shining clear

I revere, Oh God,

The strength of humankind,

Which Thou so graciously

Has planted in my soul,

That I with all my might,

May love to work and learn.

From Thee stream light and strength

To Thee rise love and thanks.

Rudolf Steiner

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. Tune in tomorrow for a lively romping, stomping morning circle!

Tags:

Day 67

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Because the Common Core Grade 1 Math Standards address addition and subtraction exclusively, they will not appear here until math blocks 3 and 4: the 4 Processes. Math blocks 1 and 2 focus on meeting the numbers up close and personal, through stories, movement, art, and hands-on activities like making real numbers. (Note that Grade 1 math could be divided into three blocks of 20 days each: Number Forms/Real Numbers/4 Processes & Practice, or four blocks of 15 days each: Number Forms/Real Numbers/4 Processes/4 Processes Practice.)

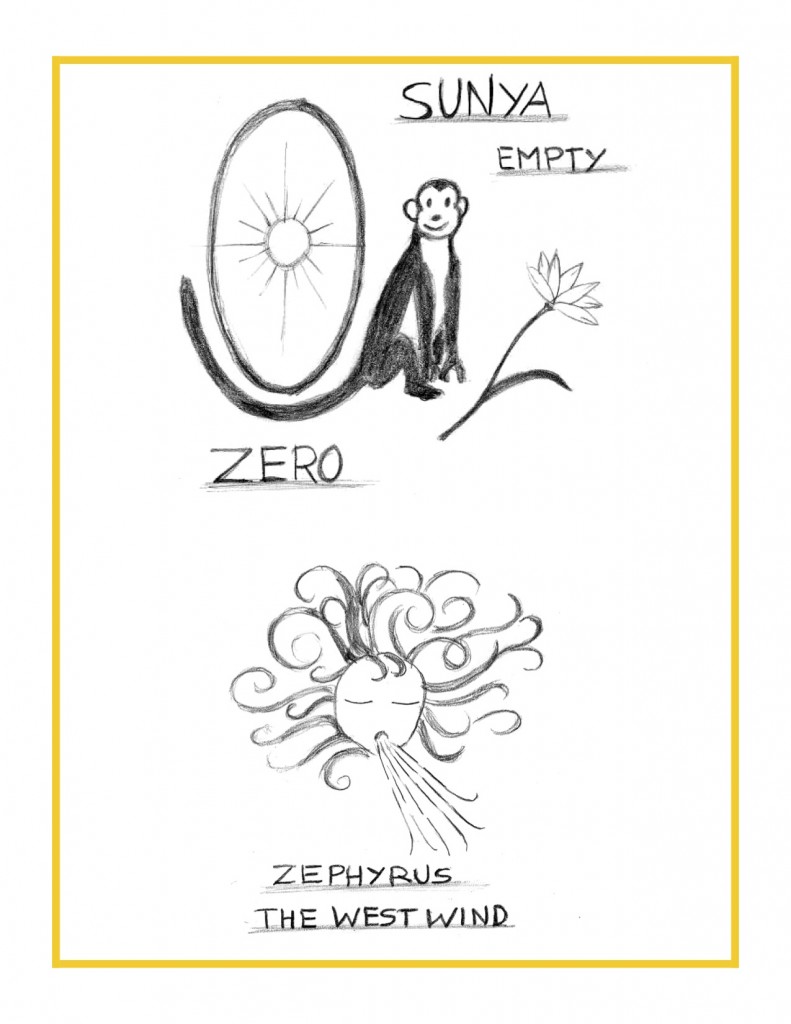

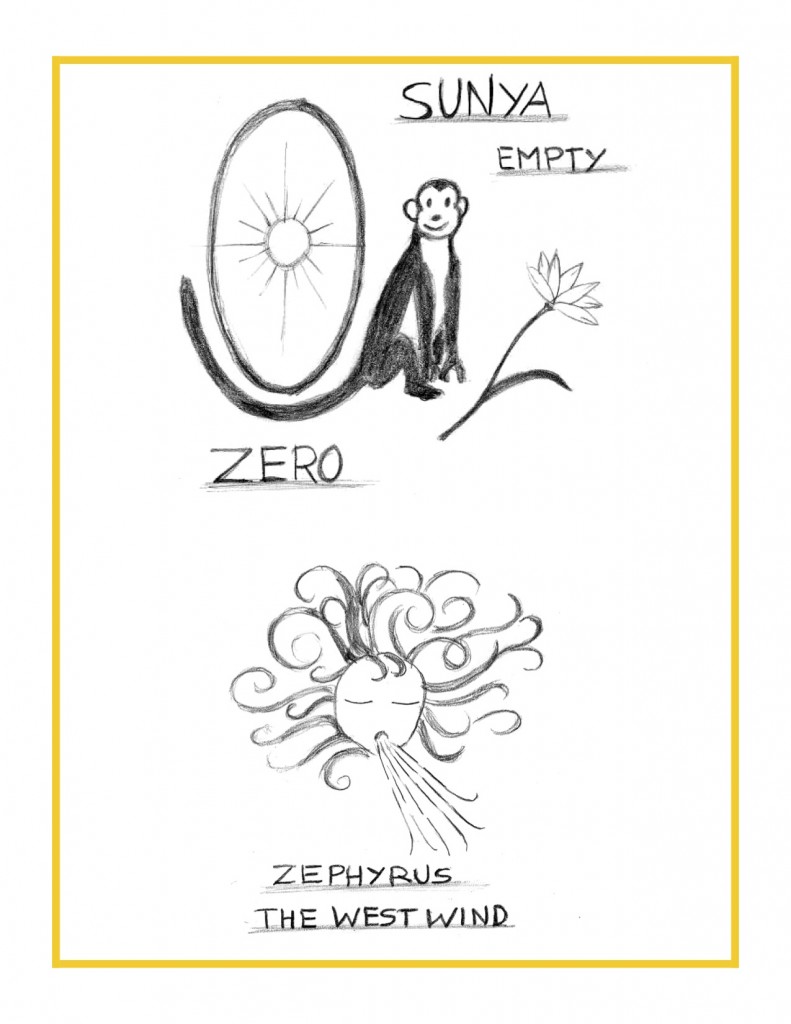

As promised yesterday, here is the child-sized story of zero. Of course, following the spiral method, the true story will emerge later on, but at age 6 or 7 this legendary version will pave the way for the factual account. And in the meantime, a heart space will be created for the concept. It is essential, as with all knowledge passed along to our children, that we transform the factual into true wisdom through the graceful medium of story and pictures.

This story is presented, along with three other stories (Roman Numerals, Arabic Numerals 1-5, and Arabic Numerals 6-10), at the very end of the first math block. Following the Waldorf method, the story is told after the previous main lesson and retold by the child(ren) the next day, as an introduction to doing the captioned drawing. See below for the suggested drawings (these drawings would actually be done in color).

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. Tune in for more Grade 1 numbers tomorrow!

The Story of Zero

Once there was a lovely land where the scent of flowers and spice filled the air, and where many different creatures lived happily together. The sun shone golden bright there as it does everywhere, but some families had very little else besides the sun’s golden riches.

Suraj, a boy whose family was very poor, had a wonderfully cheerful monkey friend named Sunya (which meansempty). Suraj chose that name because empty was how he felt a lot of the time. And when he was feeling especially sad and bereft, Suraj would find solace in his friend as he softly called his name again and again, “Sunya, Sunya, Sunya . . .”

When Suraj grew up, he discovered something that would be most important to everyone, everywhere. The gift was called sunya, which as we know means empty. Suraj, thinking about how kind the sun is to everyone, giving its riches so freely, imagined the shape for sunya should be like the sun. Suraj’s gift was given many names as it traveled, one was zifr (nothing) and another was zephyrus (west wind). Now it’s called by a name we know: zero.

Tags:

Day 66

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Because the Common Core Grade 1 Math Standards address addition and subtraction exclusively, they will not appear here until math blocks 3 and 4: the 4 Processes. Math blocks 1 and 2 focus on meeting the numbers up close and personal, through stories, movement, art, and hands-on activities like making real numbers. (Note that Grade 1 math could be divided into three blocks of 20 days each: Number Forms/Real Numbers/4 Processes & Practice, or four blocks of 15 days each: Number Forms/Real Numbers/4 Processes/4 Processes Practice.)

It could be said that we take zero for granted, as if it has been with us forever (ho-hum), but nothing could be further from the truth. Zero is a relatively new concept, adopted from the Hindus, then the Muslims. Bringing zero to the west was a truly revolutionary act, and took some time to take root, against all odds. It, along with the Arabic numerals, was roundly condemned as blasphemous and nothing short of “the work of the devil.” Here is a wonderfully told version of the story.

These are excerpts from Neatorama’s blog post, “Thanks for Nothing, The Story of Zero,” posted with permission from Uncle John’s 25th Anniversary Bathroom Reader(!) Here is Neatorama’s web address (sorry if this isn’t a live link, I’m not yet sure of how to paste links into the blog):

http://www.neatorama.com/2013/12/02/Thanks-for-Nothing-The-Story-of-Zero/#!zg6L8

Aristotle didn’t have it. Neither did Pythagoras or Euclid or other ancient mathematicians. We’re talking about zero, which may sound like nothing, but, as it turns out, is a really big something. Here’s the story.

Sometime in the early ninth century, a mathematician named Muhammad ibn al-Khwarizmi (circa 780-850 AD) gained a key piece of knowledge that would eventually earn him the nickname “The Father of Algebra.” What he discovered would also speed up mathematical calculation many times over and, eventually, make a host of amazing technological advances possible, up to and including cars, computers, space travel, and robots.

What was it? The Hindu number system (developed in India). The system intrigued al-Khwarizmi because it used nine different symbols to represent numbers, plus a small circle around empty space to represent sunya- “nothingness.” To keep from having to use more and more symbols for larger numbers, the Hindu system was aplace system. The value of a number could be determined by its place in a row of numbers: There was a row for 1s, a row for 10s, 100s, 1000s, and so on. If nine numerals and a circle to represent “nothing” sounds familiar, it should. Thanks to al-Khwarizmi, the Hindu number system (known in the West as “Arabic numerals”) is the system used in most of the world today . . .

“The tenth figure in the shape of a circle,” al-Khwarizmi wrote, would help prevent confusion when it came to balancing household accounts or parceling out a widow’s dowry. The circle was the key: If no numeral fell into a particular column, the circle served as a placeholder, as al-Khwarizmi put it, “to keep the rows straight.” A merchant (or mathematician) could run his finger down each column starting from the right and be confident that the ones, tens, hundreds, and so on, were in the correct place.

If this seems less than earth-shaking, consider this: The Hindu system was based on the abacus, a counting device that some scholars say goes back to 3,000 BC. The earliest versions used pebbles lined up in columns to represent 1s, 10s, 100s, 1000s, etc. Later version used beads strung on a wire inside a frame. With this type of abacus, when you counted past nine, you flipped one bead in the 10s column and pushed the beads in the 1s column back to nothing. British mathematician Lancelot Hogben succinctly explained what was so amazing about the Hindu circle: “The invention of sunya (zero) liberated the human intellect from the prison bars of the counting frame. Once there was a sign for the empty column, “carrying over” on a slate or paper was just as easy as carrying over on an abacus …and it could stretch as far as necessary in either direction.”

Al-Khwarizmi’s books became popular throughout the Persian Empire, and not just with mathematicians. Storekeepers, bankers, builders, architects, and anyone who needed math to do their jobs made use of Hindu numbers and al-Khwarizmi’s algebra. But it would take a surprisingly long time before his concepts spread beyond the Muslim world and into Europe . . .

Introduc(ing) Arabic numerals into the Church, replacing those unwieldy Roman numerals (was a) bad idea: using Arabic “squiggles” to do math was, to many, a suspicious indication that Sylvester II had gone over to the Dark Side. Rumors spread that while in Spain the future pope had either learned the “magic” we call math from his teacher’s secret book of magic or studied with the Devil himself . . .

Arabic numerals (and zero) made their next significant appearance in Western civilization . . . courtesy of Leonardo Fibonacci. Born in Pisa to a wealthy Italian merchant around 1170, Leonardo is said to have been the best Western mathematician of the Middle Ages (not that he had a lot of competition). Leonardo was raised in northern Africa where his father oversaw Italy’s coastal trading outposts and made sure his son was schooled in the math he would need to become an accountant. Leonardo’s Arab teachers showed him al-Khwarizmi’s Hindu-Arabic number system. “When I had been introduced to the art of the Indian’s nine symbols, knowledge of the art very soon pleased me above all else,” he later wrote . . .

That didn’t end the push back against Arabic numerals. In 1259, an edict came from Florence forbidding bankers to use “the infidel symbols” and, in 1348, the University of Padua insisted that book prices be listed using “plain” letters (Roman numerals), not “ciphers” (al-Khwarizmi’s sifr). Though Fibonacci’s book is credited with bringing zero (as well as its buddies, 1 to 9) to Europe, it took another 300 years for the system to spread beyond Italy. Why? For one thing, Fibonacci lived in the days before printing, so his books were hand written. If someone wanted a copy, it had to be copied by hand. In time, Fibonacci’s book would be translated, plagiarized, and used as inspiration for books in many other languages. The first one in English was The Craft of Nombrynge, published around 1350 . . .

Zero finally came into its own in Europe during the Renaissance when it showed up in a variety of books, including Robert Recordes’s popular math textbook Ground of Arts (1543). That book may have been read by one William Shakespeare, the first writer known to have used the Arabic zero in literature. In King Lear, the Fool tells Lear, “Thou are a 0 without a figure. I am better than thou art now, I am a Fool, thou art nothing.”

Lest we forget, advanced knowledge also developed in the New World, independently of Old World thought. The zero appears on a Mayan stela (a stone monument) carved sometime between 292 and 372 AD. That’s 400 to 500 years before al-Khwarizmi “discovered” it.

So goes the story of zero. Such a monumental milestone in human history should not be just inserted in an everyday lesson without fanfare! Shouldn’t every child know zero’s rightful history? Wouldn’t it be empowering for a 7 year old just learning numbers to know this? It should not be told exactly as recounted above of course, as it’s too abstractly adult for little ears, hearts, and minds. But it is important for you the teacher to know zero’s history and then recount it to your child(ren) in a child-sized version.

Tune in tomorrow for a child-sized version, the story of Zero as told in the Math By Hand Grade 1 Daily Lesson Plans book, with its accompanying drawings! Remember that knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal.

Tags: