Day 54

Today’s post will focus on a look at the California State and National Math Standards as a means of comparison to the Common Core Math Standards. The following is a listing of both standards as they appear in the Math By Hand binder, along with the form drawing activities and lessons and how they relate to each of the standards.

NATIONAL STANDARDS

GEOMETRY

1/ Analyze characteristics/properties of two- and three-dimensional geometric shapes, develop mathematical arguments about geometric relationships.

1/a) 1/b) 1/c)

1/a) Recognize, name, build, draw, compare, and sort two- and three-dimensional shapes.

1/b) Describe attributes and parts of two- and three-dimensional shapes.

1/c) Investigate and predict the results of putting together and taking apart two- and three-dimensional shapes.

*The geometric forms employed are two-dimensional shapes on paper, but they awaken awareness of their corresponding forms in the general environment.

*Attributes of the forms are described extensively in introductory stories.

*Symmetrical or mirrored forms can be seen as parts of the whole, taken apart.

3/ Apply transformation and symmetry to analyze mathematical situations.

3/a) 3/b)

3/a) Recognize and apply slides, flips, and turns.

3/b) Recognize and create shapes that have symmetry.

*The recognition and creation of symmetrical shapes also then transforms into forms that flip and turn from one side to the other.

4/ Use visualization, spatial reasoning, geometric modeling, to solve problems.

4/a) 4/b) 4/c) 4/d)

4/a) Create mental images of geometric shapes using spatial memory and spatial visualization.

4/b) Recognize and represent shapes from different perspectives.

4/c) Relate ideas in geometry to ideas in number and measurement.

4/d) Recognize geometric shapes and structures in the environment and specify their location.

*When the forms are moved on the floor, wonderfully complex mental images of the geometric shapes result, utilizing spatial memory and visualization.

*Shapes are seen from different perspectives in the metamorphosis drawings.

*Ideas in number are related to ideas in geometry, and ideas in measurement are sensed experientially as the forms are balanced in movement and on the page.

*While moving the forms, directions about location are freely given, while attributes of direction, such as near/far, above/below, up/down, etc., are also explored.

CALIFORNIA STATE STANDARDS

GEOMETRY

2.0) Students identify common geometric figures, classify them by common attributes, and describe their relative position or their location in space.

2.1) 2.2) 2.3) 2.4)

2.1) Identify, describe, and compare triangles, rectangles, squares, and circles, including the faces of three-dimensional objects.

2.2) Classify familiar plane and solid objects by common attributes, such as color, position, shape, size, roundness, or number of corners, and explain which attributes are being used for classification.

2.3) Give and follow directions about location.

2.4) Arrange and describe objects in space by proximity, and direction (e.g., near, far, below, above, up, down, behind, in front of, next to, left or right of).

*Many geometric forms, including triangles, squares, and circles, are experientially identified, described, and compared.

*Consistently working with the forms also allows a greater awareness of familiar, everyday objects and their relationship to the forms and their attributes.

*While moving the forms, directions about location are freely given; attributes of direction, such as near/far, above/below, up/down, etc., are also explored.

My purpose in posting this is to demonstrate the differences between the former standards and the Common Core. And to ask why we need to fix what isn’t broken. The simplicity and straightforwardness of the former standards is more than adequate to their purpose. It does make sense to have consistent standards that apply across all states, but taking a step back and reevaluating the Common Core’s efficacy and grade appropriateness may be the best approach, in light of the difficulties experienced by children, parents, and teachers with the Common Core’s implementation and methods of evaluation.

True knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. Back to the Common Core, geometry, form drawing and how they can all fit together in Grade 1. Tune in!

Tags:

Day 53

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post will focus on form drawing and the Common Core Math Geometry Standard #2, which will appear in blue, followed by its ambient counterpart.

Geometry 1.G

Reason with shapes and their attributes.

2. Compose two-dimensional shapes (rectangles, squares, trapezoids, triangles, half-circles, and quarter-circles) or three dimensional shapes (cubes, right rectangular prisms, right circular cones, and right circular cylinders) to create a composite shape, and compose new shapes from the composite shape.

Since the child is newly over the threshold of formal learning at 7, concrete rather than abstract concepts are most desirable, and it’s fair to say here that the form drawing curriculum is covert rather than overt, as befits geometry in its truest sense. All of the two-dimensional shapes mentioned above are well-covered with form drawing, and the circle is regularly divided into equal parts that represent halves, quarters, eighths, tenths, twelfths, etc. Because geometry is so complex and deeply rooted in all of being and nature, the teaching approach needs to reflect that, especially at this age. Choosing a shape on a worksheet does not fill this bill, not nearly as well as working with the more subtle forms found in form drawing.

Experiential learning is so key at this age. There’s a footnote re this standard: Students do not need to learn more formal names such as “right rectangular prism.” You might take this a step further and say that students do not need to formalize any of these terms yet, but rather get to know the shapes and their differences in a fun, friendly format. Some of the activities suggested for Kindergarten could be transposed to the Grade 1 circle time, for a more experiential, movement-oriented, hands-on approach. For instance, as suggested in the Day 18 post, either wooden or fabric three-dimensional shapes can be passed or tossed from hand to hand in the circle to gain a familiarity with their volume and perspectives when held at different angles.

To get a sense for the prismatic aspect of the cube, rectangle, cone, and cylinder, see-through objects work well. Search online for clear plastic geometry models, and add them to your shapes collection. (Some of these models can be used later on for exploring volume as well.) Put two or more of these models together to form other shapes (as in 2 cubes together make a rectangular prism).

I must say that I was able to much more easily align the Math By Hand materials, activities, and lesson plans with the California State and National Math Standards. Perhaps the intention of the Common Core to be more rigorous has created significant challenges with implementing it. Standards and testing have long been perceived by some as tangential to true learning. This seems especially true of alternative educational systems, many homeschoolers, and most unschoolers. My personal take in creating Math By Hand was that when used properly, the standards can provide the bones of a good education, that are then fleshed out and brought to life with good teaching.

I don’t get this sense from the Common Core Standards. They are simply not as user-friendly, accessible, or holistic, but rather seem to be a reflection of the times in their focus on the parts over the whole. I have found volumes and volumes of material online re lesson plans for the Common Core, but none of it rings quite true. When I was a Waldorf classroom teacher, the preparation time was daunting since no worksheets or textbooks are used, and ideally the teacher follows the class through the grades. In order to keep things in balance, I needed to modify the time spent on prep. I’m afraid that so many prep hours are needed with Common Core that teachers are shortchanging the above mentioned “fleshing out” part of teaching. As I have now tonight put in too much time on this post!

Yes, balance seems key, as does allowing knowledge to ensue rather than be so diligently pursued. Remember, true knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. Tune in tomorrow for more Grade 1 form drawing and geometry!

Tags:

Day 52

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post will focus on the form drawing block, which begins the Grade 1 year. The child(ren)’s willingness to take on the task of learning shines as the teacher or parent is recognized as the authority who can impart that knowledge and wisdom. Form drawing is an apt way to begin, with its emphasis on the deep recognition of geometry in its truest sense: as “geo” earth, “metry” measurement. The Common Core Math Standard will appear in blue, followed by its ambient counterpart.

Geometry 1.G

Reason with shapes and their attributes.

1. Distinguish between defining attributes (e.g., triangles are closed and three-sided) versus non-defining attributes (e.g., color, orientation, overall size); build and draw shapes to possess defining attributes.

The forms are introduced in a variety of ways, through story and movement. After an overall image is imparted through a simple story, the form is intuitively grasped with the teacher’s help, and then moved, running or walking, large on the floor, usually within the parameter of the large (at least 4 feet in diameter) circle. After the form is run on the floor, it’s drawn in the air with a crayon, and finally drawn on paper. In this way, distinctions can be made by the child(ren) between the sizes drawn on the floor with their feet, in the air, and on paper.

The first and most essential element learned in form drawing is the difference between the straight line and curve, and the realization that everything everywhere is made up of one or the other or both. The straight line and curve drawn together is the first form, then many variations of that follow, establishing the solid grounding and confident ability to know and master versions of the main element of all being, its form. Structured forms follow: the circle, square, triangle, hexagram, etc., many of them juxtaposed in relation to numbers. The circle is related to the number 1, the triangle to the number 4, the hexagon to the number 6, to name just a few. Shapes are built and drawn to possess their attributes most effectively, by using all the senses and movement to learn them.

After 3-4 weeks of being immersed in the forms that make up universal structure, the child(ren) proceed with confidence on a first venture into learning. Form drawing can be brought back every Monday to reinforce this grounding and orientation as a means of centering and focusing on the current subject.

True knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. Tune in tomorrow for more Grade 1 form drawing and geometry!

Tags:

Day 51

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post will be brief.

I am in overload mode, having traded my Mac G5 desktop for a Macbook. So here I sit with the laptop on my lap in totally unfamiliar territory, never having used one. I’m so non-techie, it’s a wonder I can navigate the cyber world at all. But I do think it’s nicer, sitting here on our comfiest couch rather than scrunched up at my desk on the desktop!

As for embracing the new and unfamiliar, I came across this quote from Erich Fromm the other day. “The quest for certainty blocks the search for meaning. Uncertainty is the very condition to impel man to unfold his powers.”

It strikes the same chord for me as Rudolf Steiner saying that good teaching is like standing in the rain without an umbrella. What I’ve taken away from this is that the best teaching happens when the teacher is vulnerable to the learning process. Nothing inspires a child more than to see a teacher’s or parent’s hard-won striving.

In light of this, we might consider that all the testing and teaching to the test that’s been so prevalent in our schools of late flies in the face of these wonderfully hopeful thoughts.

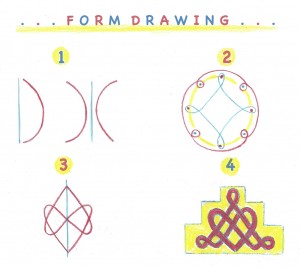

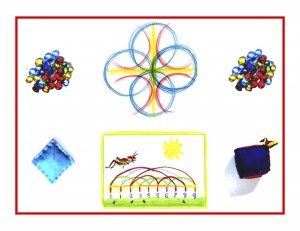

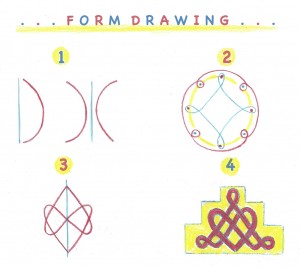

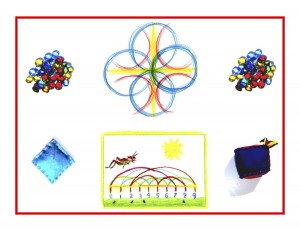

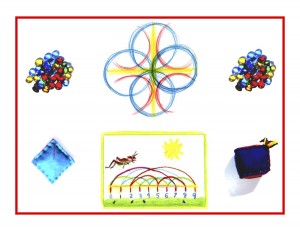

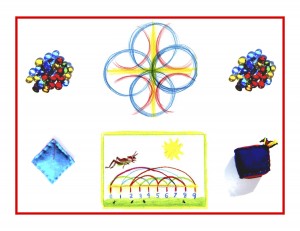

Tomorrow I revamp my office to accommodate the new space and configuration, and then move on to business as usual. Not to depart too terribly far from the blog theme though, I will leave with a small gallery of form drawings to set the stage. These four drawings represent the progression from Grades 1 to 4.

Hoping this sneak preview has whetted your appetite for more Grade 1. And remember that true knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. See you tomorrow for form drawing and Common Core geometry!

Tags:

Day 50

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post will focus on a bit of backstory from the Grade 1 section of the Math By Hand binder before starting our year with form drawing and the Common Core Geometry Standards.

The 3 Rs. They do play a big role in Grade 1, as ‘Riting, Reading, and ‘Rithmetic. Letters and numbers, as the building blocks, though they may already be known on some level, are now introduced formally, while imparting relationships and deeper, foundational meanings. The letters can be taught one by one. No rush, since they will be read and written lifelong, and if the first association is positive, it will remain so. First, a story is chosen that fits the letter. For example, a King could be selected to represent the letter K, as it lends itself beautifully to the form. A regal arm outstretched, one foot forward, a flowing robe, and crowned head make the K. It’s drawn large on the page as the K and the King, surrounded by other elements and/or details from the story. If this context is used, letter formation will flow, with the story holding the letter in place, unencumbered by reversals or mistakes. Reading is then taught through writing, as familiar parts of the story are copied into books and illustrated.

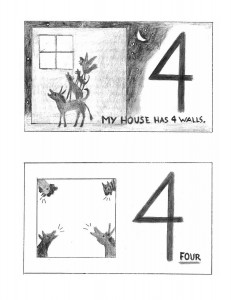

Numbers can be introduced similarly to the letters; the numbers 1-12 could be illustrated with specific stories. “East of the Sun and West of the Moon” for example, might convey the idea of one-ness. The numbers, like the letters, could be drawn in special books, large, with the story illustrated on a facing page. The special quality of each number might also be demonstrated by a form drawing, such as a triangle representing 3, a square, 4, a hexagon, 6, etc. In this way, story and art helps impart meaning to the abstract numbers, so that an interest in and a love for them will naturally follow. (See below for examples of the 4 and 6 with story and geometry illustrations.) After the numbers 1-12 are learned in this way, and the nature and differences of the cardinal and ordinal numbers experienced, counting can be taught in lively, natural partnership with movement, recitation, and singing.

Rhythmic recitation and movement are excellent aids to learning counting and the times tables. Since math (or arithmetic) is rooted in the rhythmic system, it blends well with music, rhythmic speech, and movement. An excellent way to learn the 3s, for example, is walking in a circle, stamping and clapping every 3rd number while quietly whispering and stepping the in-between ones.

Waldorf curriculum often works with the 4 temperaments. Representing fairly universal traits that are readily recognizable, they are the phlegmatic, melancholic, choleric, and sanguine temperaments. There’s a deeper quality as well, perceived in their interactions with each other. Applying these traits to the processes not only enlivens their conceptual aspect, but will bring identification that deeply resonates with 6-7 year old children. All 4 might be identified as follows:

Addition or Plus, phlegmatic, is GREEN (and always growing)

Subtraction or Minus, melancholic, is BLUE (sad, or deeply thoughtful)

Division or Divide, choleric, is RED (decisive or even bossy)

Multiplication or Times, sanguine, is YELLOW (busy, happy, flighty)

Jaunty hats and pouches add to the fun, as stories are acted out and the character of each process is seen. Pouches are filled with counting stones, shells, or gems, and calculation has begun.

Can 7-year-olds learn to knit? Yes! After making wooden needles with dowels and beads, they learn simple stitches through imaginative verses and stories, knit a small rectangle, fold and sew it, and stuff it with wool. A sitting cat! There’s pride of workmanship and improved eye-hand coordination, along with brain development and stimulation. All of the arts subjects offer many such benefits, while bringing endless enjoyment and enthusiasm. The time spent playing games, in gym class and recess, also reaps many rewards along with being just plain fun.

Hoping this sneak preview has whetted your appetite for more Grade 1. And remember that true knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. See you tomorrow for form drawing and Common Core geometry!

Tags:

Day 49

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post will focus on the introductory overview for Grade 1. Note that the Common Core Standards will appear in blue, followed by an ambient translation.

In Grade 1, instructional time should focus on four critical areas: (1) developing understanding of addition and subtraction within 20; (2) developing understanding of whole number relationship and place value, including grouping of tens and ones; (3) developing understanding of linear measurement and measuring lengths as iterating length units; and (4) reasoning about attributes of, and composing and decomposing geometric shapes.

In my Catholic school Grade 1 picture, I am one of sixty(!) students. There are twenty seven boys standing around the perimeter in white shirts and ties, and thirty three girls seated at desks in white puffed sleeve, peter pan collar blouses and pleated navy blue jumpers. It was orderly! It had to be with one little nun in charge. I learned a lot from the good sisters, up though Grade 12, but I did not ever learn to love (or even like) math.

Math and movement must go together, especially in the early grades. Math wants to sing and dance and play, and it is in this context that I will strive to “ambientify” it. In this blog, all posts up through Grade 4 will be close in content and style to the Math By Hand curriculum, which is mainly Waldorf-inspired (along with other alternative approaches).

Some major differences distinguish Waldorf from mainstream education, such as: (1) simple, one-digit multiplication and division are taught alongside addition and subtraction; (2) place value waits until Grade 2; (3) formal time and measurement does not appear until Grade 3; (4) geometric shapes are not directly addressed but are thoroughly covered with form drawing.

(1) Students develop strategies for adding and subtracting whole numbers based on their prior work with small numbers. They use a variety of models, including discrete objects and length-based models (e.g., cubes connected to form lengths), to model add-to, take-from, put-together, take-apart, and compare situations to develop meaning for the operations of addition and subtraction, and to develop strategies to solve arithmetic problems with these operations. Students understand connections between counting and addition and subtraction (e.g., adding two is the same as counting on two). They use properties of addition to add whole numbers and to create and use increasingly sophisticated strategies based on these properties (e.g., “making tens”) to solve addition and subtraction problems within 20. By comparing a variety of solution strategies, children build their understanding of the relationship between addition and subtraction.

Discrete objects are good tools for learning how to count and calculate, but if the objects used are natural rather than man-made, they can better serve more than one purpose. Cute, colorful, plastic teddy bear counters serve the purpose but may also be distracting. And any opportunity to connect children back to nature should be taken, because “nature deficit disorder” is real, and troubling.

Re plastic connecting cubes, yes these and other materials like them are widely used by many innovative math programs, including Montessori. But their use may abstract something that perhaps should not be abstracted: the depth and dimensionality of number and math. So if their purpose is to impart meaning to math functions, meaning may be more likely to be met with Waldorf methods such as attributing different personalities to each of the 4 processes.

Increasingly sophisticated strategies such as “making tens” may be too cumbersome and clumsy for now. I saw examples of this online (i.e., finding the total of 8 + 6 by making ten trades to arrive at the answer using 10 + 4 instead), and found it to be a circuitous method, frustrating for both children and their parents. Children crying over hours of homework, and parents wringing their hands over not understanding the method themselves, does not make a pretty picture. Comparing a variety of solution strategies may happen in a more integrated way as the deeper relationships between the processes are understood.

(2) Students develop, discuss, and use efficient, accurate, and generalizable methods to add within 100 and subtract multiples of 10. They compare whole numbers (at least to 100) to develop understanding of and solve problems involving their relative sizes, they think of whole numbers between 10 and 100 in terms of tens and ones (especially recognizing the numbers 11 to 19 as composed of a ten and some ones). Through activities that build number sense, they understand the order of the counting numbers and their relative magnitudes.

Again, multiplication and division are added into the mix along with addition and subtraction, so that a working relationship involving equivalency and proofs may be in place from the very beginning. The concepts of “greater / less-than” can be learned in a concrete, pictorial way, as can counting the teens to 20, or the differences between the cardinal and ordinal numbers.

(3) Students develop an understanding of the meaning and processes of measurement, including underlying concepts such as iterating (the mental activity of building up the length of an object with equal-sized units) and the transitivity.

(It’s footnoted that, “Students should apply the principle of transitivity of measurement to make indirect comparisons, but they need not use this technical term.” (Whew! I’d better hone my understanding of it as well . . .) Though measurement and time will not be formally introduced until Grade 3, a solid foundation will be built in Grade 1 with various experiences and activities.

(4) Students compose and decompose plane or solid figures (e.g., put two triangles together to make a quadrilateral) and build understanding of part-whole relationships as well as the properties of the original and composite shapes. As they combine shapes, they recognize them from different perspectives and orientations, describe their geometric attributes, and determine how they are alike and different, to develop the background for measurement and for initial understandings of properties such as congruence and symmetry.

Geometry is not made conscious and executed with instruments until Grade 6 in the Waldorf method. But the foundations are laid, strong and deep, with form drawing. Starting with a month of main lessons in Grade 1, and continuing once a week from Grades 1 – 5, forms are explored and compared in every possible combination and relationship.

True knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. On to Grade 1 tomorrow!

Tags:

Day 48

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post will focus on a brief overview of the Waldorf Grade 1, along with a suggested block plan schedule. Here’s what makes up the year:

Upper case printed letters.

Form drawing.

The numbers to 100.

The 4 Processes.

Fairy or folk tales.

Knitting, painting, drama, flute and singing, foreign languages, gym/games.

The main lesson/block plan format is child (and teacher/parent) friendly. The main lesson focuses on one academic subject at a time, in a 1 1/2 to 2 hour block in the morning. Here’s a typical Grade 1 day:

20 minutes / morning circle / singing, recitation, lots of movement, skills practice.

1 1/2 to 2 hours / main lesson / 3 to 4 weeks long.

20 minutes / recess / preferably outdoors.

20 minutes / skills practice.

1 hour / lunch.

open ended / the fun stuff / knitting, gardening, field trips, gym/games, arts/crafts.

Here is a suggested block scheduling plan for the year (blocks can vary from 3-4 weeks):

September / form drawing.

October / writing and reading.

November / math / the numbers.

December / handwork.

January / writing and reading.

February / math / the 4 processes.

March / nature studies.

April / writing and reading.

May / math / 4 processes practice.

June / class play.

Block planning is beneficial and efficient. Learning occurs in the morning when both the child(ren) and teacher/parent are awake, alert and ready to learn. The pace is reverent, respectful, and relaxed because really, there’s no hurry. Learning happens best when it just happens. Trust and faith make the best schoolmasters in Grade 1. Really. Strong belief in your and your child(ren)’s ability to teach and learn is paramount!

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. All the posts, from tomorrow on, will be organized into ambient math lessons and activities for each of the three math blocks listed above, aligned to the Common Core Math Standards.

Tags:

Day 47

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today is the first day of Grade 1, which will be structured differently from the Kindergarten posts, following a block plan format. The Common Core standards will again be addressed one by one.

The Waldorf Grade 1, 6-7 year old is ready for structured learning, eager to begin to take on the world and all there is to learn in it. This transition is a momentous one, so it’s appropriate to begin with a 3-4 week block of form drawing. Main lessons are 1 1/2 – 2 hours long, in the morning, after a brief circle time.

Form drawing will be the focus of this post. Block plan scheduling and the main lesson format will be described in detail over the next few days. The following is excerpted from the Grade 1 Form Drawing and Stories book.

Form drawing promotes an awareness of archetypal forms, enhancing eye-hand coordination and creativity. Forms are introduced through images and stories, translated to movement, traced in the air, and finally drawn on paper. The story or image provides a picture of the form, thereby making it more accessible. Using large motor movements to introduce new concepts incorporates a spatial orientation that effectively transitions later on to working with fine motor skills.

Simpler forms can be run very large, on the floor or ground, indoors or out. Many forms can be contained within a circle or other visual parameters, which can be drawn on the floor or the pavement with chalk. Running the forms is an effective technique that is also helpful with letter and number formation. For the mirrored/symmetrical forms, the teacher moves the form on one side while the student watches, mirroring the movement on the other side.

The beginning drawings in Grade 1 illustrate the idea that all things are made up of straight or curved lines or some combination of the two. Vertical symmetrical or mirrored forms are drawn on one side and mirrored on the other. They improve balance, spatial orientation, and eye-hand coordination, while forms with invisible lines help develop control and mastery, along with fluidity and flexibility.

See below for some examples of Grade 1 form drawing. Each one can be introduced along with a story that expresses its uniqueness. The top left form could be described as a “A Sunrise,” the straight, radiating lines form an invisible half circle. The top right form, “A Butterfly,” a vertical mirror image. The middle left, “Brother and Sister Pine Trees,” graduated vertical straight lines. The middle right, “Ram’s Horns,” another mirror image. And the bottom form, “A Falling Leaf” or a swing, vertical motion in curved lines.

Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. More Grade 1 tomorrow!

tomorrow!

tomorrow!

Tags:

Day 46

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.” Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful.

Well readers, please allow me a bit of a vent/rant tonight. Melt-downs happen to all of us, and I happen to be in the middle of one right now. Precipitated by 10 hours writing the entire 2013 Math By Hand bookkeeping ledger in prep for tomorrow’s tax appointment, a daunting week dealing with Common Core issues, and a cyber space, existential moment of deep doubt: is anyone really out there reading this?

I will elaborate on the middle issue only, since it’s the focus of this blog, and because the others are merely(!) self-doubting feelings that will pass (they always spontaneously seem to somehow). Math By Hand’s base consists primarily of homeschool and Waldorf homeschool families. We sell almost exclusively through the website to individual families, and to a lesser degree to publicly funded, charter school homeschool families.

A homeschool charter school teacher wrote and asked last week if I would be aligning Math By Hand with the Common Core. This was/is disturbing to me. The Math By Hand binder contains an extensive California and National Math Standards section with thorough and detailed alignments to all the lessons and activities. If I do take on the significant task of rewriting/revising the existing standards to the Common Core, what happens if the current storm of unhappiness and problems among teachers, parents, and students results in the Common Core being modified or perhaps even replaced?

It’s questionable whether a Waldorf or Waldorf-inspired curriculum can successfully align with the Common Core. I suppose it can, if testing is held off until the end of third grade (which happens to be the “match-up” year for Waldorf with public school students). The main purpose of this blog is to provide alternative, “ambient” ways to fulfill the Common Core Math Standards. I am fully confident that if the K-2 grades cover the standards with alternative, arts and movement rich lessons and activities, and are not test-prepped or tested until third grade, the children can pass the tests at that point. (This is not to say that the testing is an accurate measure of an excellent education however.)

There seems to be a lot of controversy among parents, teachers, and mostly hapless children who are subjected to the “rigor” of Common Core teaching and testing. I read a lot of stories online last week, and am so sad and frustrated with the plight of the little ones who are sat down from 5-7 years old and made to suffer the childish confusion of wanting desperately to do what’s asked of them, but are not up to the task!

One concerned Kindergarten Dad posted pages from his daughter’s workbook and, with some comic relief, questioned the sense and validity of the worksheets, along with the cost of the workbook ($30) and the cost to his daughter who is repeatedly reduced to tears over trying to “perform at grade level.” Take a walk online, look and listen to what’s going on out there. I do think the controversy is good if it can wake us up to the realization that our littlest ones need to be little. They need to move, hop, skip, jump, sing, laugh, play, and be merry.

Here’s an excerpt from my first blog post that bears reposting: I believe that the “back door” or indirect approach is a very effective teaching tool, especially with math. Most children will happily and eagerly take on any task if it’s presented in a friendly, warm, and meaningful way.

The Race to the Top, espoused by the Common Core Standards, is a most direct approach. This approach does not translate well, whether in a classroom or homeschool environment. As Viktor E. Frankl says in Man’s Search for Meaning, “Don’t aim at success. The more you aim at it and make it a target, the more you are going to miss it. For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side effect of one’s personal dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the by-product of one’s surrender to a person other than oneself . . .”

In light of this, knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal. On to Grade 1 tomorrow!

And . . . children should be blowing bubbles, not filling them in.

Tags:

Day 45

For one year, 365 days, this blog will address the Common Core Standards from the perspective of creating an alternate, ambient learning environment for math. Ambient is defined as “existing or present on all sides, an all-encompassing atmosphere.” And ambient music is defined as: “Quiet and relaxing with melodies that repeat many times.”

Why ambient? A math teaching style that’s whole and all encompassing, with themes that repeat many times through the years, is most likely to be effective and successful. Today’s post, as a farewell to the Kindergarten, features Bruno Bettleheim’s thoughts on why fairy tales are the best fare for a young developing mind. And to close, the wonderful Grimm’s tale, “The Bremen Town Musicians,” used as the Math By Hand / Grade 1 introduction to the number 4 (see the accompanying Grade 1 drawings at the bottom). If this tale is told a number of times in the Kindergarten, it will be reassuringly familiar when it comes again the following year.

Taken from the Math By Hand / Grade 1 introduction to the fairy tales for the numbers 1-12,

“Bettelheim says that the child’s mind, rapidly expanding into new fields of knowledge and experience, fills the resultant huge gaps in understanding with fantasy. This impulse finds a true friend in the fairy and folk tale. Beginning with realistic scenarios, such as a mother sending her daughter off alone to Grandmother’s, or a father and stepmother worrying about not having enough food for themselves and their two children, (“Little Red Riding Hood” and Hansel and Gretel”) the story inevitably escalates into a fantastic world of animals who speak, evil witches in candy covered houses, frogs who are enchanted kings, and other wonderful flights into a world where disbelief is willingly suspended. The hero of the story, (often a boy or girl, or a kind-hearted, simple soul) after facing many trials and tribulations, always wins in the end. Thus, fantasy is given free reign, with events in the story that are far more challenging than any real life has to offer. A child has difficulty absorbing abstract facts and reasoning, since the capacity to understand them is not yet sufficiently developed. These stories, rich in symbolic pictures, carry comfort and conviction, whereas “facts” are usually confusing, thus causing greater uncertainty. The story of Jack the Giant Killer is more reassuring to a fearful child than simply stating the fact that there are no giants. Jack is a small boy pitted against a huge, fearful giant. He wins his life (and riches as well) by cleverly using his wits.”

Though this may be off the math subject, I’d like to contrast the above sentiment to that of presenting a Kindergartner with a worksheet or an assessment test. These mistaken interpretations of the Common Core are causing much heartache and pain, to children and parents alike. It may be true that the Common Core Standards do not inherently demand that the concepts they offer be drilled and then tested, but unfortunately this is indeed how the Common Core is largely being interpreted. Now let us escape to the wonderful world of “The Bremen Town Musicians” . . .

A certain man had a donkey, which had carried the corn sacks to the mill indefatigably for many a long year. But his strength was going, and he was growing more and more unfit for work. Then his master began to consider how he might best save his keep. But the donkey, seeing that no good wind was blowing, ran away and set out on the road to Bremen. There, he thought, I can surely be a town-musician. When he had walked some distance, he found a hound lying on the road, gasping like one who had run till he was tired. “What are you gasping so for, you big fellow,” asked the donkey. “Ah,” replied the hound,” as I am old, and daily grow weaker, and no longer can hunt, my master wanted to kill me, so I took to flight, but now how am I to earn my bread?” “I tell you what,” said the donkey, “I am going to Bremen, and shall be town-musician there. Go with me and engage yourself also as a musician. I will play the lute, and you shall beat the kettle-drum.” The hound agreed, and on they went. Before long they came to a cat, sitting on the path, with a face like three rainy days. “Now then, old shaver, what has gone askew with you,” asked the donkey. “Who can be merry when his neck is in danger?” answered the cat. “Because I am now getting old, and my teeth are worn to stumps, and I prefer to sit by the fire and spin, rather than hunt about after mice, my mistress wanted to drown me, so I ran away. But now good advice is scarce. Where am I to go?” “Go with us to Bremen. You understand night music, you can be a town-musician.” The cat thought well of it, and went with them. After this the three fugitives came to a farmyard, where the cock was sitting upon the gate, crowing with all his might. “Your crow goes through and through one,” said the donkey. “What is the matter?” “I have been foretelling fine weather, because it is the day on which our lady washes the child’s little shirts, and wants to dry them, said the cock. But guests are coming for Sunday, so the housewife has no pity, and has told the cook that she intends to eat me in the soup tomorrow, and this evening I am to have my head cut off. Now I am crowing at the top of my lungs while still I can.” “Ah, but red-comb,” said the donkey, “you had better come away with us. We are going to Bremen. You can find something better than death everywhere. You have a good voice, and if we make music together it must have some quality.” The cock agreed to this plan, and all four went on together. They could not reach the city of Bremen in one day, however, and in the evening they cam to a forest where they meant to pass the night. The donkey and the hound laid themselves down under a large tree, the cat and the cock settled themselves in the branches. But the cock flew right to the top, where he was most safe. Before he went to sleep he looked round on all four sides, and thought he saw in the distance a little spark burning. So he called out to his companions that there must be a house not far off, for he saw a light. The donkey said, “If so, we had better get up and go on, for the shelter here is bad.” The hound thought too that a few bones with some meat on would do him good. So they made their way to the place where the light was, and soon saw it shine brighter and grown larger, until they came to a well-lighted robbers’ house. The donkey, as the biggest, sent to the window and looked in. “What do you see, my grey-horse,” asked the cock. “What do I see?” answered the donkey. “A table covered with good things to eat and drink, and robbers sitting at it enjoying themselves.” “That would be the sort of think for us,” said the cock. “Yes, yes. Ah, if only we were there,” said the donkey. Then the animals took counsel together how they should manage to drive away the robbers, and at last they thought of a plan. The donkey was to place himself with his fore-feet upon the window ledge, the hound was to jump on the donkey’s back, the cat was to climb upon the dog, and lastly the cock was to fly up and perch upon the head of the cat. When this was done, at a given signal, they began to perform their music together. The donkey brayed, the hound barked, the cat mewed, and the cock crowed. Then they burst through the window into the room, shattering the glass. At this horrible din, the robbers sprang up, thinking no otherwise than that a ghost had come in, and fled in a great fright out into the forest. The four companions now sat down at the table, well content with what was left, and ate as if they were going to fast for a month. As soon as the four minstrels had done, they put out the light, and each sought for himself a sleeping-place according to his nature and what suited him. The donkey laid himself down upon some straw in the yard, the hound behind the door, the cat upon the hearth near the warm ashes, and the cock perched himself upon a beam of the roof. And being tired from their long walk, they soon went to sleep. When it was past midnight, and the robbers saw from afar that the light was no longer burning in their house, and all appeared quiet, the captain said, “We ought not to have let ourselves be frightened out of our wits,” and ordered one of them to go and examine the house. The messenger finding all still, went into the kitchen to light a candle, and, taking the glistening fiery eyes of the cat for live coals, he held a match to them to light it. But the cat did not understand the joke, and flew in his face, spitting and scratching. He was dreadfully frightened, and ran to the back door, but the dog, who lay there, sprang up and bit his leg. And as he ran across the yard by the dunghill, the donkey gave him a smart kick with its hind foot. The cock, too, who had been awakened by the noise, and had become lively, cried down from the beam, “Cock-a-doodle-doo!” Then the robber ran back as fast as he could to his captain, and said, “Ah, there is a horrible witch sitting in the house, who spat on me and scratched my face with her long claws. And by the door stands a man with a knife, who stabbed me in the leg. and in the yard there lies a black monster, who beat me with a wooden club. And above, upon the roof, sits the judge, who called out, bring the rogue here to me. So I got away as well as I could.” After this the robbers never again dared enter the house. But it suited the four musicians of Bremen so well that they did not care to leave it any more.

With this we say farewell to the Kindergarten, and begin looking at first grade tomorrow. Knowledge ensues in an environment dedicated to imaginative, creative knowing, where student and teacher alike surrender to the ensuing of that knowledge as a worthy goal.

Tags: